The Three Ships

In the first half of the 19th century the exploits of three real pirate ships so captured the imagination of the populace they altered the course of story telling for the next two centuries. These events to some extent obscured that the source of the ‘lost treasure island’ legend had originated from Lord George Anson’s file . The three ships were,

1. 1822: The Araucano, which turned pirate and sailed into the Pacific Ocean.

2. 1826: The Peruano, which was taken from Callao into the Pacific Ocean.

3. 1828: The Defensor De Pedro, a pirate ship in the mid Atlantic Ocean.

The technology of communication for this period tended to be word of mouth. This, combined with the romance of the treasure two of these ships were supposed to be carrying, as well as the fact all the events occurred in the same decade, caused things to get a little mixed up. Details of one ship got blended in with the details of the others consecutively so that what is supposed to be an accurate retelling of an event can be found to contain the identifiable parts of another. These real events then need to be studied to learn what the correct details are for each. Then their offspring, the resulting stories from the late 19th century, need to be absorbed.

The Templar Legacy

In one of the closest escapes in history not all Templars were imprisoned by King Phillip’s henchmen for the entire Templar Naval fleet at the port of La Rochelles made to the safety of the sea but they certainly did not disappear.

The Templar Naval flag was that of a skull and crossed thighbones. Though sounding a bit grim it merely identified the ship as belonging to the Templars as it just represented the Templar sepulchral custom of placing the skull and (crossed) leg bones of a deceased brother in the communal ossuary.

Nevertheless, so incensed were the Templars at the Pope’s betrayal that they never forgave nor forgot and as long as they were able mercilessly descended upon any of the Pope’s ships unfortunate enough to cross the path of a ship flying the Skull and Crossbones.

In what has now become the universal symbol for piracy we see the legacy of the escaped Templar fleet living on. Continuing to strike terror into the hearts of the sailors of the Spanish galleons during the golden age of piracy, variations of the theme were adopted by all the famous pirates for their personal flags. The misnomer of calling a skull and crossbones flag the ‘Jolly Roger’ was due to it being associated with the French name of a signal flag hoisted by pirates to give the warning ‘No Quarter Given’, in other words, ‘Surrender or all will die’. This flag, a plain red field, was the dreaded ‘Joulie Rouge’ (pretty red).

In what must be one of the greatest examples of irony this symbol now transcends the years due to its association with legends that tell of a lost ‘pirate’ treasure buried on an island that is, as you now know, the treasure of the Templars themselves.

The Araucano

In 1822, the Chilean Navy was under the command of Admiral Cochrane. Captain Robert Simpson commanded one of the warships, the ‘Araucano’. In that year the crew turned pirate and attacked the town of Loreto where Simpson was abandoned. The Araucano then sailed into history.

It seems that besides the usual victims, the ship targeted the treasures of Peruvian churches. With enough treasure to satisfy every man on board, they made sail for Honolulu, changing the name of the ship en route to the more tranquil Providence. In Hawaii, the authorities became suspicious causing the captain to up anchor and sail to the south. They eventually arrived at Huahine, in the Society Islands. There again, the ways of the crew created problems. Often drunk, they bragged about having a stolen treasure aboard. The captain, concerned with the need to appear respectable, made every effort to ingratiate himself with the English missionaries working on the island. Trouble over one of the native women however resulted in several men being killed. They sailed east again, towards the Tuamotus and Marquesas islands.

On the way they stopped at Tupai, then uninhabited, where according to legend they buried treasure. This allowed them to make for Tahiti where they could get rid of the ship that had become a liability. The captain made out to the other ships in Papeete’s port they wanted to join a seal hunting expedition that was being formed. The plan was to seize one of the other ships and set sail for Tupai. The plan was thwarted however when the Providence was seized. The surviving mutineers managed to flee back to Huahine where they convinced the missionaries that their previous conduct was due to the orders of their officers. Some stayed working on the island for years, whilst others slowly drifted away. As far as is known none were able to return to Tupai and recover the treasure. Tupai is in one of the ‘Trinities’.

The Peruano

The main source for the story is one Gabriel Lafond de Lurcy and appears in Volume 7 to 8 of his collected works titled ‘Quinze ans de Voyages autour du Monde’ which was published in 1851. The ship in the story was the ‘Peruano’ but the name can get anglicised into ‘Peruvian’. The name of the main protagonist was Andrew Gordon Roberton, a Scot.

De Lurcy was a 19th century adventurer and a contemporary of Roberton during the wars of independence in South America. De Lurcy first met Roberton in 1820 when Roberton, as a First Lieutenant in the Peruvian Navy, boarded an American ship that Lurcy was an officer upon. An exceedingly bold and capable captain, Roberton was further described as having fiery red hair and permanent repugnant grin. By 1826 Roberton was now serving in a peacetime navy and became besotted with a beautiful woman, Teresa Mendez, in Callao. Mendez roundly snubbed him at a gathering of naval officers due to his lowly status and pay. A Lieutenant Veyra jokingly remarked that Roberton would have no trouble winning over the desired lady if he took over the Peruano. It was known that the Peruano, which lay in the harbour, was carrying war funds totaling two million piastres. Lurcy said Roberton’s response was to politely smile at this remark.

At dawn the Peruano was found to be missing but a longboat soon rowed into the harbour carrying the officer and six crew members that had been guarding the ship. Roberton and a party of his own men had silently boarded the ship in the early hours of the morning to overpower the watch. When the ship was far out at sea the crew were set free to ignominiously row back to shore. Roberton headed the ship to Tahiti where the crew drunkenly caroused with the Polynesian women. Knowing that the Peruano would be the target of an organised search, Roberton ordered his two trusted henchman, Williams and Georges, to round up the crew. Eight drunken and befuddled sailors were dumped in the longboat and towed out to sea as the Peruano sailed away from Tahiti. Faraway from land with no food, water or sails the longboat’s tow line was cut. Roberton explained to the other sailors onboard the Peruano that he had detected a mutinous plot so the action had been done to protect them all. Roberton headed the Peruano towards the Marianas islands, singling out Agrihan Island.

Dropping anchor at Agrihan, the gold was ferried ashore by longboat and carried a short distance through the vegetation to be buried at the foot of a cliff. Symbols were cut into the trees and rocks to mark the path to the location as well as at the location itself. A sum of 20,000 piastres was withheld onboard the Peruano for contingency purposes.

Setting sail again, a course was set to Hawaii during which Roberton instigated a plan to eliminate the rest of the crew. Overpowering them, they were bound and sealed below decks before the ship was scuttled. Roberton, Georges and Williams rowed ashore in the longboat to pass themselves off as shipwreck survivors.

They next took a ship to Rio de Janero, where Georges ‘disappeared’. Next, Roberton and Williams obtained passage on a British Convict ship bound for Sydney. Sydney was a busy maritime port and Roberton was of conspicuous appearance so it was decided that they should head to a quieter location, the southern island city of Hobart. There, Roberton met a fellow scot named Thomson. Thomson had once been the captain of a whaler but was now reduced to eking out a living with the small fishing yawl he owned. Roberton chartered Thomson’s ship for a journey to Agrihan but beyond that the purpose of the trip was not disclosed. Williams by this stage had been reduced to an alcoholic and one night whilst in his cups divulged enough information for Thomson to suspect the reason for the voyage. A short time afterwards, Williams somehow ended up overboard and was unable to be saved by Roberton, who sadly informed Thomson of the tragedy. During a hand of cards one night, things came to a head when Thomson disclosed his knowledge of the treasure. In a flash, Thomson found himself overboard also with the armed Roberton preventing the yawl’s crew from bringing the ship around to save him. Thomson treaded water as he watched his ship sail away.

Fortune was on Thomson’s side as a Spanish ship carrying Senor Medinilla, the Governor of the Marianas, later picked him up. After Thomson told his story the amazed Governor set off in pursuit of Roberton, running down the small ship just off the island of Saipan. Roberton was no longer onboard, having rowed ashore in an effort to escape. Hunted down by an armed party of Spaniards, Roberton gave up without a fight. Back on board the Spanish ship, Roberton was flogged until he bent to their requests to take them to the treasure. Placed in irons, Roberton was held below until the ship arrived at Agrihan. There, Roberton failed to lead the search party to the treasure choosing instead to wander aimlessly around the island. He was taken back to the ship and flogged again until he promised compliance.

Shackled in heavy chains, Roberton shuffled across the ship’s deck to the longboat that was waiting to row him back to the island. As he was being lowered to the longboat he kicked off the boat’s gunwale to precipitate a fall into the sea. A Spanish sailor who plunged after him only managed to grasp a few hairs from Roberton’s head as he sank to the depths.

The basic facts about Roberton and the event of the theft of a ship named the Peruano are correct. The main source was De Lurcy writing in his Quinze ans de Voyages autour du Monde. He was around as a first-hand witness when all this was happening. When De Lurcy visited the Philippines in the 1830s he also learned that Medillina had organised a search of Agrihan for the treasure, employing some 600 native labourers for the task. De Lurcy obtained most of the account in 1828 from a beachcomber in Oahu (Hawaii). This beachcomber claimed to be the sole survivor of the crew that had been set adrift in the longboat. Miraculously, he had been rescued by a passing New Bedford whaler, more dead than alive.

The latter details of the story provided by the beachcomber about the Peruano and Roberton after they left Callao therefore should be viewed with some degree of skepticism. A diversion for nautical storytellers of the time was to create incredulous sounding tales placing themselves as the protagonist. Herman Melville, one of the great storytellers of that era, himself gave a cautionary warning to others of the propensity of beachcombers to exaggerate their tales or their grasp of local knowledge to try to impress their listener.

The Defensor de Pedro

In 1827, Benito de Soto was a crewman upon the slave ship ‘Defensor de Pedro’ that was taking onboard its human cargo from the coast of Africa. The captain went ashore to supervise the loading whereupon the mate and De Soto mutinied. Those who did not to take part in the mutiny were put off in the longboat. De Soto soon shot the mate to take command of the ship. The cargo of slaves was soon disposed of in the West Indies realising a good price, save for one boy De Soto reserved to be his servant.

They attacked many other vessels. The treatment of one, an American brig, exemplified the peak of their atrocities. Having plundered all the valuables, they hatched down all the hands into the hold, except a black man who was allowed to remain on deck to provide a spectacle. Setting fire to the brig, they watched as the miserable African climbed the ropes and shrouds trying to escape the flames. Exhausted, he finally fell into the now open and flaming hold to the shouts of De Soto and his crew.

The following year they fell upon a vessel, the ‘Morning Star’ near Ascension Island. The Morning Star was a British vessel on a passage from Ceylon to England. Besides carrying a valuable cargo, also on board were several passengers consisting of a Major and his wife, a surgeon, some civilians and twenty five invalid soldiers with three or four of their wives.

As the Morning Star was unarmed it attempted to flee but was soon run down. De Soto put a round of grapeshot across her decks as a warning. Calling over the captain and the mate to the Defensor de Pedro, both were slaughtered.

Back on the Morning Star, those who survived the pirate’s initial onslaught were secured below deck. The females were locked in the roundhouse on deck. Beaten, bleeding and terrified, the men lay huddled together in the hold while the pirates proceeded in their work of pillage. Some two hours of labour saw the Morning Star emptied of its valuables during which time the ship’s store of liquor was emptied down the pirate’s throats. The women were all ravished, their screams reaching the ears of the trapped and helpless men.

De Soto had remained aboard the Defensor de Pedro during the proceedings but had issued orders that none on board the Morning Star were to be left alive. By the time De Soto called back his crew they had wasted so much time drinking and indulging themselves that instead of murdering everyone they just locked the women in the cabin and heaped heavy lumber on the hatches of the hold. The pirates expected that all trapped onboard would be killed when the Morning Star sank as they had bored some holes in the ship below the waterline. Returning to the Defensor de Pedro they sailed off into the approaching night leaving the Morning Star to settle in the water.

Unbeknownst to the pirates the women had managed to break out of the cabin and soon freed the men. Working the pumps, the Morning Star was kept afloat despite six feet of water in the hold. The next day they were rescued by another vessel that safely took them all to England.

De Soto, upon discovering his orders had not been carried out, immediately put about to return to the Morning Star. No sign could be seen of that vessel so De Soto consoled himself with the belief that she was now at the bottom of the sea, many fathoms below the cognisance of the Admiralty Courts.

De Soto and his ship continued on their course of piracy. At Corunna he disposed of a great part of the booty, obtained false papers, then set out for Cadiz to dispose of the rest. Caught in a storm, they wrecked on the coast not far from that city. Representing themselves to be honest shipwrecked mariners to the authorities at Cadiz, they were met with some sympathy. De Soto even negotiated a contract for the sale of the wreck but before the money was paid suspicion of them arose due to inconsistencies in the account they gave of themselves. Six of the crew were arrested, six escaped to the Carraccas and De Soto, with one of his crew, fled to the neutral ground before the fortress of Gibraltar. Gaining entrance to the fortress by false papers, he now came under the jurisdiction of English law. Living in an inferior tavern, he was taken prisoner after a maidservant observed the chattels in his room carried different names. He was kept in gaol for nineteen months whilst evidence was gathered against him. One of those appearing in the court as part of the prosecution was the young boy slave De Soto had used as a servant. De Soto pleaded his innocence up to the day before his execution but the certainty of his fate and the awful voice of religion finally subdued him. He made an unreserved confession of his guilt and became truly penitent. As he stood on the cart below the gallows he murmured “Adios todos” (Farewell all) then leant forward to facilitate the fall.

Confusion reigns

By the late 19th century and early 20th century there tended to be a generic version of a story going around which was a homogeneous blend of these three events. This story spoke about a large treasure being buried on an island in the 1820s. Already, a form of this story has been encountered in the tales that have in their plot a pirate who dies leaving a map to a treasure island. Generally Cocos Island, some 550klm south west of Costa Rica in the Pacific, was nominated as being the place where the treasure lay, but some other locations were named also.

This overall generic story version could have two major limbs branching off it known as ‘The Loot of Lima’ and ‘Benito of the Bloody Sword’.

‘Benito of the Bloody Sword” also had its own odd sub-branch. Each of these two major limbs could be found being treated as though they were entirely independent of each other even though they both shared common details. During the heyday of treasure hunting expeditions, the 1920s and 30s, nobody seemed to regard it as anything but a coincidence that the same details could be found appearing in both limbs. Then again, not much thinking at all appears to have been done because none of the stories ever seem to have been compared with actual history.

History does record though that there actually was a treasure Callao in the 1820s but it was never stolen. Lord Cochrane, formerly of the Royal Navy, was Commander-in-Chief of the Chilean Navy during the time when Peru was fighting for its independence from Spain. Much to the chagrin of Lord Cochrane, General San Martin (the liberator) allowed the Spanish to remove their accumulated treasure from the fort in Callao a full three weeks after Lima’s independence was declared. The incident is recorded in Lord Cochrane’s diary for the 19th of August 1821 where he wrote,

“The Spaniards today relieved and reinforced the fortress of Callao and coolly walked off unmolested with plate and money to the amount of many millions of dollars—in fact, the whole wealth of Lima—which, as has been said, was deposited in the fort for safety.”

Lord Cochrane also makes no mention of any of the Spanish treasure being subsequently stolen by pirates. No other writer in Peru at that time records any mention of a sizeable Spanish treasure being stolen either.

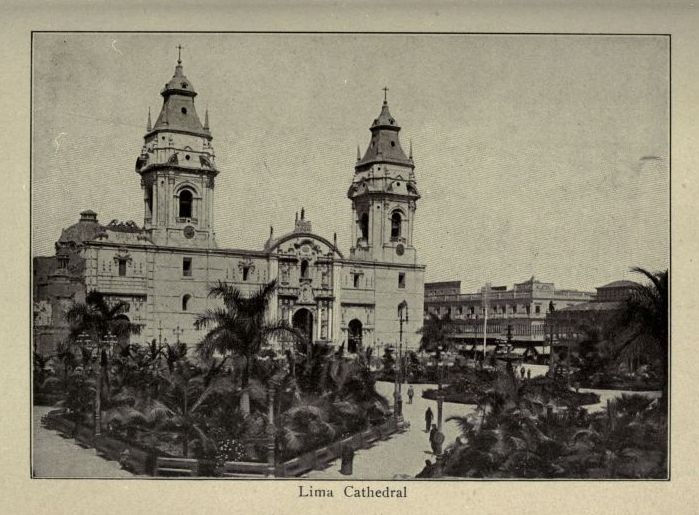

Lieutenant Harry E. Rieseberg was famous around the middle of the 20th century as a salvage diver and treasure hunter. He also was the author of treasure hunting books and one of the few people to do some real research into the Loot of Lima story. Visiting the Cathedral at Lima he was astounded to discover that at no time had the Cathedral ever been plundered. A priest even pointed out the life-size effigy of the Golden Virgin Mary along with the twelve Golden Apostles, which according to a version of the Loot of Lima story was supposed to have been stolen. At Rieseberg’s request the British Vice-Consul at Lima, A. Stanley Fordham, made further inquiries among people familiar with the history of Peru. These included the head of the Peru National Library who was generally regarded as the best-informed authority on Peruvian history. All those contacted agreed that there was no connection between Lima and any treasure said to be buried on Cocos Island.

Add that to the knowledge of the real events of the Three Ships and the distorted ‘lost treasure’ stories that circulated at the time take on a truly ludicrous dimension.

The Loot of Lima

This story is problematic as there are numerous versions of the legend known as the ‘Loot of Lima’, all more or less accepted as being genuine. The best reference book on the subject is ‘The Lost Treasure of Cocos Island’ (1960) written by Ralph Hancock and Julian Weston. A quote from their book says it all,

“If all the versions (all Thompson) so far written about the Lima treasure on Cocos Island were printed in one book, you couldn’t carry it. And if all the stories about all the treasures hidden on Cocos Island were published and the profits put in one bag, it would make another sizeable treasure.”

Unfortunately the authors came with the preconceived notion that the treasure did exist on Cocos Island so just went on to examine various aspects of known accounts. They concluded that a particular version of the legend involving a character named Forbes was the real history of the matter.

The following is a generic version of the Loot of Lima story that begins around the time of the event that Lord Cochrane witnessed; the removal of the treasure from the fort in Callao.

The Spanish were seeking to repatriate their accumulated wealth back to Spain so a British merchantman ship was chartered for the task. Named the Mary Dear (Other accounts may give ‘Mary Dyer’, ‘Mary Dier’, ‘Mary Deer’ even ‘Mary Read’ etc) it was commanded by a Scot, one Captain William (or Marion) Thompson (or Thomson, Tompson etc)

Thompson was well known and trusted by the Peruvians having traded for three years along the coast. This stood him in good stead with them and for a good price took on board the church treasures of Lima. Such was the treasure’s size it took two days to stow onboard. Some soldiers and priests were assigned to accompany the treasure on the trip to ensure it reached its destination. Soon after leaving Callao, Thompson’s cupidity took over and he succumbed to the temptation of the vast treasure in the hold. The guards and priests were murdered. Another version has the mate, James Alexander Forbes, inciting the crew to mutiny. Thompson was asked “Are you with us or the sharks?” Thereafter, Thompson became Forbes’ puppet.

Knowing that the Peruvian authorities would soon hunt them down Thompson sailed to Cocos Island to hide the treasure.

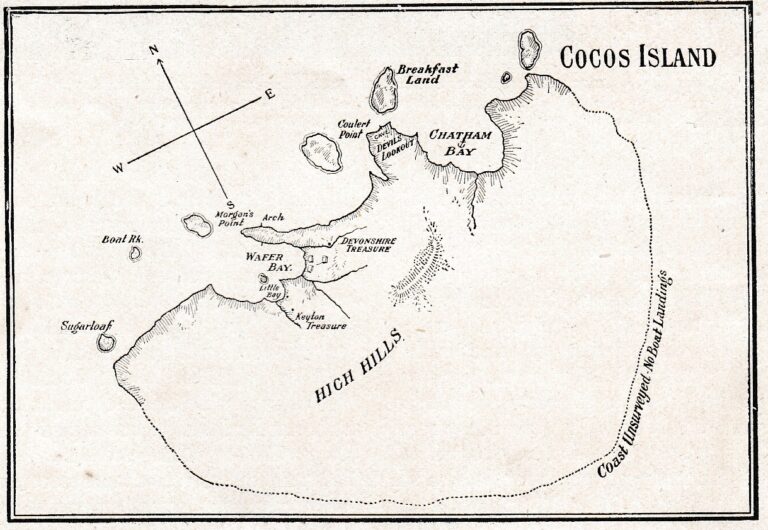

Anchored off Chatham Bay (or Wafer Bay or The Bay of Hope) it took numerous trips to land all the treasure on the beach. Some say it was buried on the beach, others say it was beneath a large rock marked in a special way, for others it was in a cave or in a vault with an ingenious pivoting stone slab for a door.

Numerous versions exist of what happened next:

• a Peruvian Royalist warship caught up with them after they left the island. Taken back to Callao, 8 were shot. Thompson and two others were spared on promising to reveal the hiding place of the treasure. Thompson told them it was hidden on the Galapagos Islands. He escaped, served on a whaler and eventually made it home to Nova Scotia.

• They scuttled the Mary Dear then rowed to the mainland to pose as shipwrecked mariners (It is about a three day sail in favourable weather).

• a Spanish man-of-war that had escaped Admiral Cochrane’s blockade caught up with them. Put to trial, all were hung except Thompson and the mate who bargained their lives in exchange for leading the Spanish to the treasure.

Accounts of Thompson and the mate/others then being forcibly returned to Cocos may take this form:

• On the island they somehow escaped from the landing party. They evaded capture for a number of weeks until the Spanish (or Peruvian Royalists) gave up and left. Eventually, a British whaler that called at the island for fresh water rescued them. They were put ashore at Puntarenas. Forbes/the mate etc died in hospital of yellow fever.

The story then jumps about 20 years forward in time to Newfoundland where Thompson makes an appearance in conjunction with a person named as John Keating.

Born in 1808 in Harbour Grace (Isle of Newfoundland), Keating moved to St John’s where he worked as a ship’s carpenter before becoming a captain. The stories suggest that the now elderly Thompson had been wealthy but had fallen on desperate times. Keating cares for the declining Thompson. On his deathbed, Thompson confides to Keating the secret of the treasure, passing a map and directional instructions to him.

Sometime in the 1840s Keating sets sail for Cocos Island in the brig Edgecombe with a Captain Gault or Gould in command. Also on board was one Boag (or Bogue, even Boig), ship owner and/or captain. He or they were Keating’s partner/s in the venture.

Again there are different versions as to what happened next. Keating and Boag found the treasure as per Thompson’s instructions. Boag was murdered by Keating or drowned in the surf, or they both hid on the island to avoid Gault and the crew who they knew would demand a share. They/Keating eventually got away from the island in the ship’s longboat with what treasure they/Keating could carry without causing suspicion. Boag’s name then disappears inexplicably from some of the narratives.

We next hear of Keating back in Newfoundland where he is said to have disposed of some Spanish gold coins, evidence that he had indeed found the treasure. He is believed to have made at least two further trips to Cocos. A Judge Prowse of Newfoundland said, “I have heard persons describe the astonishment of Keating’s wife when he threw all the gold and jewels on the bed for her to see.” The proceeds from these trips enabled Keating to purchase a farm, several commercial properties and a schooner.

Another account of Keating gives the detail that in 1846 Keating, in company with a man named Bogu, fitted out a small schooner for the ostensible purpose of pearl-fishing in the Bay of Dulce.

Judge Prowse also had something to say about Bogue,

“Bogue and his wife I recall very well, they being one of the handsomest couples I have ever seen. They sailed for the North Pacific, ostensibly on a bear-hunting expedition to Dulce Bay, but made an excuse to call at Cocos Island to replenish their water casks….”

In 1894 Nicholas Fitzgerald made his appearance and advanced the story of Keating. Fitzgerald was described as being a Harbourmaster of St John’s, Newfoundland and he said he met Keating in 1868. Fitzgerald had found Keating in Codroy Village. Sheltering in a deserted house, his bed a sail on the floor, Keating was now penniless after a shipwreck caused the loss his schooner and crew. Caring for Keating, Fitzgerald was invited on a future expedition to the island. Fitzgerald declined, in a letter to a friend he said,

“I thought I would be running grave risk of my life to go single-handed with him. The disappearance of Boag was unsatisfactorily explained to me by him…”

When Keating died he bequeathed to Fitzgerald the directions to find the treasure in Catham Bay on Cocos Island. After Keating’s death, his second wife came out to announce she likewise had documents giving the directions to find the treasure. Her documents said it was to be found in Wafer Bay. Fitzgerald examined the wife’s directions and said they were useless as only he held all the necessary directions.

The two most important names from the Loot of Lima story in this overall investigation are John Keating and Nicholas Fitzgerald. Their place and actions in the scheme of things needs to be understood. John Keating’s involvement in this mystery is a lot greater than as it just appears in these popular accounts. After saying Keating successfully recovered some of the treasure, the stories merely use him as a device to show the information from ‘Thompson’ was an unbroken chain. This device causes a paradox in the overall story that is never explained; Keating was said to have followed Thompson’s directions to find the treasure but when Keating freely passes on those same directions to others they prove useless. Something unexplained has happened and it leaves only 2 options:

1. Keating passed on deliberately misleading information.

2. Keating never passed on information willingly at all; it was just obtained from him somehow.

Option 2 produces a consideration that is worth exploring. If the information was just obtained from Keating this does not necessarily include circumstances conducive to reliable or correct transmission. Impolite circumstances such as theft, threat or eavesdropping can have this effect and also goes some way to identify the cause of the story’s paradox by then including Option 1.

Nicholas Fitzgerald is important for another reason. Numerous ‘authentic’ maps, directions and statements all purporting to have come from Keating were in circulation at the time, all just rehashing the standard story. For example a letter he wrote on 23rd May 1898 gives these rather fanciful details,

“The cave, if found without the door being damaged or blown up, will surprise all who see it, on account of the ingenious contrivance and workmanship, possibly done by Peruvian workers in stone, whose skill was noted. In Keating’s words, the cave is between twelve and fifteen feet square, with sufficient standing room. The entrance to it is closed by a stone made to move round in such a peculiar manner that it sets in to the rock when you turn it, leaving a passage through which one man can crawl into the cave at a time, and when the stones is turned back into its place, the human eye cannot detect it; it fits like a paper on a wall….Keating told me that the first time he went to the island he had no trouble in finding the cave; but the second time, there had been a disturbance or eruption which changed the features of the place, but he found it all the same.”

It is know known that Fitzgerald did obtain some real directions from Keating, a version of these Charroux published in his book ‘Treasures of the World’ . As shown in the above letter, Keating also supplied to Fitzgerald a lot information designed to deliberately misdirect him.

Everything about the Loot of Lima legend may appear as a hopeless muddle of real and imagined events. What are supposed to be accurate accounts are even somewhat muddled. The following is an extract from ‘The Book of Newfoundland’ (1937) by J.R.Smallwood. Written with the assistance of C.H. Hutchings, a grandson of Boag, it informs us that,

“Arriving in Panama, the Captain, second mate (W. Boag Jr.) Keating and Gault went ashore to see the British Consul. A squall upset the boat, and they were thrown into the sea. Keating, Johnny Boag and Gault managed to right the boat and climb into her. Boag Sr. being a good swimmer swam a mile to the land and to safety. The other three in the upturned boat were rescued by the first mate of the Edgecombe, who heard their cries and put off to the rescue from the ship in another boat. Captain Boag was drowned. He is said to have been pushed from the half-submerged boat by Keating and was devoured by sharks.”

No wonder Boag disappeared from the stories if his grandson couldn’t even make any sense.

The variation in the spelling of the name from ‘Boag’ to ‘Bogue’ just follows the pronunciation of it. ‘Boig’ is an interesting variation that seems to have come about due to the name of two real Scottish brothers, John and William Doig who were local colour at the time the story of the Loot of Lima is set. The Doigs had immigrated to Peru where they became merchantmen. John commanded his own warship in Lord Cochrane’s squadron and attacked Spanish shipping. There is a story in the family that John eventually returned to Scotland with a huge wealth garnered during his time in South America.

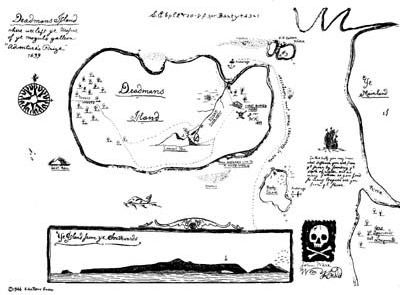

Early maps depicted Cocos Island as being somewhat skull shaped. This is the reason why the name of the ‘lost treasure island’ was popularly referred to as ‘Skull Island’ or ‘Deadman’s Island’.

The Thought

Of more import is the strange but true claim made upon the Royal Bank of Scotland in 1965. The story of a ship named the ‘El Pensamiento’ (The Thought) and its fantastic cargo gives a fascinating demonstration of how the cross pollination of details can occur from one story to another. However unlike most associated stories where a treasure ship is said to go to some unknown location this one has a mysterious treasure arriving at a very well known location.

In 1965, a legal action was raised by Senora Violeta Aguilar de Caceras of Lima, Peru, who claimed from the bank “598 large merchant bags which were dispatched from Lima, Peru, in 1803 by the ship El Pensamiento under Captain J Fanning and J Doigg to the Royal Bank of Scotland and delivery entrusted to Castillo de Rosa”.

Another simultaneous claim of the treasure said it had been shipped from Lambayeque, Peru by a Corregidor named Antonio Pastor y Marin de Segura, Marques de Llosa. John Fanning and John Doig jointly commanded the ship, ‘El Pensamiento’. It was the descendants of de Segura, who died in 1804, that were also laying stake to the treasure pursuant to a 5th generation will. Contained in 90 wicker baskets the treasure was said to be deposited in the bank by a Sir Francis Mollinson or Mollison.

Bank of Scotland officials had to deal with solicitors, South American banks, the Peruvian consul, the Procurator Fiscal of Edinburgh and tellingly the Masonic Grand Lodge of Scotland acting for its South American brothers.

A search made of the bank’s vault and strongrooms in Edinburgh and Glasgow did not turn up the missing treasure but enabled the bank to say they had checked. Safe custody books were of no use either in settling this strange case as these only went back to 1860.

No treasure or settlement was forthcoming and all ended up viewing the incident as an ‘experincia simpatico’, an interesting shared experience.

De Segur and Fanning are all real persons and along with Doig were well known seafarers.

Benito of the Bloody Sword

Benito Bonito, is the melodramatic name given for the next character in the other major limb of the overall ‘lost treasure’ story being circulated in the 19th century. Benito Bonito is mainly associated with Cocos Island again but the name does appear for some other curious locations. If the story of the Loot of Lima was bad enough to make you wonder why anyone would think it was real, then ‘Benito of the Bloody Sword’ is even worse. ‘Benito Bonito’ somewhat translates as ‘Beautiful Ben’ but the only reason that can be found as to why Benito de Soto’s name was so exoticly garbled is just that of romantic invention. Not much is ever presented in the way of proof in the various accounts other than the circular assertion that the treasure is Benito’s because he buried it. The main source for the story of Benito’s treasure on Cocos Island is a German, one August Gissler. He went there in 1888 to spend 17 years searching for the treasure. He permanently left the island in 1905 with his wife who had lived there with him. He died in New York in 1935. During all that time on the island he claimed that all he ever found were 33 Spanish gold coins and a gold gauntlet. These were sold in order to obtain provisions. He was known as ‘The Hermit of Cocos Island’ but by formal presidential decree in 1897 he was appointed the island’s first and only Governor.

The most detailed account of the story that inspired Gissler to search Cocos Island appears in Hancock and Weston’s book. To work through it you have know that though the name of the pirate given in the first part of Gissler’s account is ‘Dom Pedro’, the story is just another version in the Benito Bonito family of tales. In many versions Benito Bonito’s ship is named as being the Relampago (Lightning), the same name that is given to Dom Pedro’s. One version says that Dom Pedro was Benito’s baptismal name. The name is most likely a garbling of the name of Benito de Soto’s ship, the Defensor de Pedro.

In 1880 Gissler, on route from London to Honolulu, became friendly with a young Portuguese man named Manoel Cabral who had embarked in San Miguel in the Azores. Cabral told Gissler he wanted to find an island called ‘La Palma’ which was about four days sail from Guayaquil. Confiding in Gissler the full reason for his voyage, Manoel eventually produced a bundle of papers sewn up in an oilcloth. The papers consisted of a long letter and an autobiography written by Manoel’s grandfather (called Manoel also). The letter finished with the grandfather expressing the hope that little Manoel would seek out the treasure whose location was detailed in the papers. The papers had been passed on to little Manoel on the death of his grandfather. Several months later Gissler had managed to get a syndicate together. In February of 1889, the barque Wilhemina and a syndicate of 14 arrived off Cocos. Again the wind failed and it was over four weeks before they were able to land on the island.

One of the syndicate, who knew Spanish, translated old Mac’s map,

“This island lies in latitude N. 5 deg. 27 min. longitude W. 87 deg. It is a healthy place. In the year 1821 we buried here a treasure of immense value. After we had buried the treasure we planted a coconut tree on top and took bearings by compass which showed locations to be N.E. by E. ½ E. to the east mountain and N. 10 deg. east to the West Mountain.”

After a month on the island the constant battle against tropical downpours, heat, tangled undergrowth and insects took its toll. The majority of the syndicate gave up. Gissler remained enduring the rigours of Cocos Island for the next 17 years. He never found any treasure.

What is pretty obvious is that Gissler had never read Treasure Island by Robert Louis Stevenson. If he had, he might have noticed a disturbing similarity in the bearings he was given by old Mac and those on Captain Flint’s treasure map:

“Tall trees, Spy-glass Shoulder, bearing a point to the N. of N.N.E. Skeleton Island E.S.E and by ten feet.”

Another version from the Benito Bonito family of stories shows the literary device employed to include the name Thompson. This account gives the year as being 1816. Benito was the Mate of a Portuguese trading brig. After a quarrel, he slays the captain and takes command of the vessel. He attacks an English slaver, the Lightning. The entire crew is executed save for Thompson, an Englishman and Chapelle, a Frenchman, who agree to side with the pirates. The ship’s name is retained by Benito but in its Spanish form, Relampago. Benito begins his rampage up and down America’s Pacific shores. During a raid on a coastal town he learns that a large consignment of gold is to be shipped from Mexico City. Disguised as muleteers the pirates seize the shipment. They then head the Relampago for Cocos Island where the booty was divided into three portions. A serious argument arises over the division of the spoils on the island. Benito hides his share of the loot in a cave. Benito then abandons the worst of the troublemakers on the mainland. Eventually the British warship H.M.S. Espiegle corners the Relampago. Rather than being hung from the yardarm, Benito chooses to blow his brains out on his own quarterdeck. All the crew are executed save Thompson and Chapelle who plead the defence of duress (that they were forced into being pirates). Chapelle is last heard of in San Francisco in 1841 where he leaves behind certain papers purporting to relate to hidden treasure before he departs to the South Seas. Thompson is said to have gone to live in Samoa and changed his name to McComber.

Benito, both Bonito and de Soto, do sometimes get mentioned for hiding their ill gotten gains on Trinidade Island. The story told by the dying pirate in ‘The Cruise of the Alerte’ can be recognised as a loose version of the Loot of Lima legend with Trinidade Island being named instead of Cocos Island. As de Soto sailed the Atlantic it just flows his name would end up being associated with Trinidade Island if there were tales of a treasure being buried there. It doesn’t make any sense though for Benito Bonito to decide to bury a treasure but then sail it all the way from the Pacific to the Atlantic before he does so.

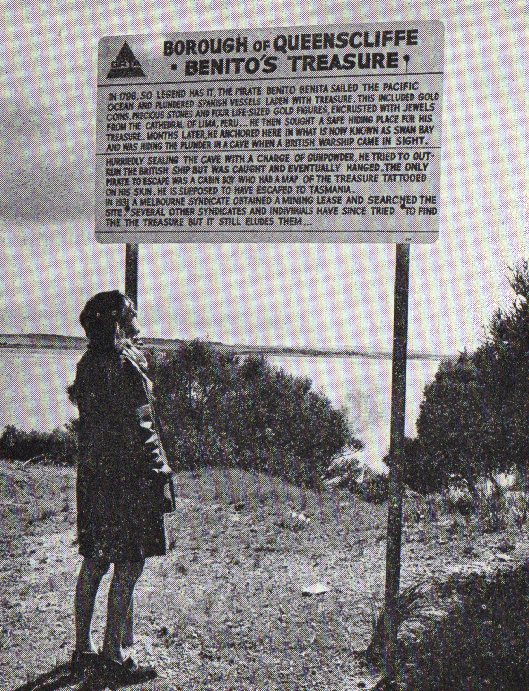

That isn’t the furthest Benito Bonito was said to sail before he buried his treasure. In the lower south-east corner of Victoria, Australia is Queenscliffe, a seaside town in Port Phillip Bay. At one stage the Geelong Regional Tourist Authority had even erected a signboard on the peninsula that separates the subsidiary Swan Bay from the much larger Port Phillip Bay due to the strength of the local legend.

The story was said to have been started by one person named John Karisimo who was known to the locals as ‘Stingaree Jack’. Stingaree Jack had spun to them a story of his piratical adventures and how he had escaped from a Spanish ship with the map to Bonito’s treasure tattooed on his arm. The treasure was to be found in a ‘rock topped cave’.

Captain Bennett Grahame alias Benito Bonito

Mary Welch (and husband) appeared in San Francisco in 1853 where she told the an intriguing story to those who would listen.

In 1818, Captain Bennett Grahame was sent to the Pacific in command of the HMS Devonshire to conduct a survey mission. Grahame and his crew adopted a course of piracy instead. A warship sent to deal with him was defeated, the surviving crewmembers joining Grahame. A handsome devil, Grahame was the identity behind the name everyone mistakenly referred to as Benito Bonito. This was just the latinisation of Bennett as in ‘good looking Bennett’. The Devonshire took on some Spanish galleons laden with gold and silver. Even though they were defeated the Devonshire was extensively damaged. Grahame transferred his command to one of the Spanish ships named Relampago. The Relampago sailed to Cocos Island and an encampment was made. The island became Grahame’s base of operation. Accompanying Grahame was the young Mary Welch and she was there when the treasure was hidden. To protect the treasure it was placed in a chamber at the end of a tunnel. The face of a cliff was blown down with gunpowder to seal the entrance. Three British warships were eventually dispatched to deal with the Relampago and they cornered Grahame in the Bay of Buena Ventura. Just prior to his capture Grahame passed his treasure chart to Mary as it was unlikely she would be searched intimately. Taken to England the crew were tried, convicted and hanged. Mary Welch was sentenced to twenty years of penal servitude and transported as a convict to Tasmania. After her sentence had expired she married. Now, as an old woman, she was in the United States to raise interest in her recovery of the treasure. On Cocos Island Mary’s map was useless. She said everything had changed so much she could no longer recognise the site.

The English were still on the case though as Queen Victoria wanted the missing hoard. In 1897 armed parties from HMS Imperieuse and HMS Amphion landed on Cocos Island. Following a map, they tried to excavate down to find an engraved slab that marked the tunnel to the cavern containing the treasure. Nothing was achieved other than the creation of a diplomatic incident. On board HMS Imperieuse was a young officer, Reginald Hall, who established the way modern British Intelligence functions.

By the 20th century confusion reigned. Ralph D. Paine in his ‘The Book of Buried Treasure’ (1911) was telling everyone that Thompson of the Mary Dear, after burying his Loot of Lima treasure on Cocos Island, joined up with Benito Bonito. Thompson managed to escape when Benito Bonito was captured, which allowed him to go on to have that fateful meeting with Keating many years later.

What has been covered now is enough information to understand the significance of the Three Ships from the 1820s and their influence upon the fantastic stories that sprouted about a missing treasure that same century. Those stories themselves have now been examined and exposed for what they are, imaginative tales that have deep within them small parts of the real history of the great lost treasure.