King Charles II of Spain

When Charles II died, with him died the line of Habsburgs who had ruled Spain since 1506 though Phillippe de Bourbon, Duc of Anjou had been named previously by Charles II as successor. A grandson of the reigning French king Louis XIV and of Charles’ half-sister, Maria Theresa, Louis XIV himself was an heir to the Spanish throne through his mother, daughter of Philip III. Even so, this sparked off the War of the Spanish Succession (1701-1714). After the 13 year war the Frenchman Phillippe de Bourbon was crowned Philip V of Spain.

Ubilla, that worthy Knight of Santiago, was not impressed by what had occurred and in 1714 surreptitiously removed some important items that were proof of a King’s sovereignty from Spain and took them to the ‘opposite’ side of the world: 42 north latitude to 138 west longitude.

Times were constantly changing for all and the history of the Spanish military orders and particularly the operation of 19th century politics against them suggest a reason for the mission carried out by the Spanish captain known to us as Diego Alverez.

In Spain, the Bourbon dynasty continues today to reign (in the form of a constitutional, democratic monarchy) via Juan Carlos I, full name Juan Carlos Alfonso Víctor María de Borbón y Borbón-Dos Sicilias. The Bourbons themselves know very well that permissive reigns can be tenuous.

In 1808 a Bonapartist Monarchy under Joseph Napoleon ousted the Bourbons from ruling Spain. The Bourbons were restored after the defeat of Napoleon and even managed to survive the dictatorship of Francisco Franco.

Under Napoleon Spain’s four Military Orders were suppressed and their properties confiscated. This suppression was the first of what was to be an ongoing pattern of suppression then reestablishment of the Orders by successive monarchs, regents or governments which saw them change from being established forces at arms that held strategic parcels of land to organizations of merely honorific title.

We will pick the history up when Ferdinand VII re-establishes the Orders and their properties upon the Bourbons recovering the crown of Spain in 1814.

In 1829, Ferdinand VII married his niece Maria Christina of the Two Scililies. When Ferdinand VII died in 1883 Maria Christina ruled as regent for their daughter Isabella.

In 1836 Maria Christina attempted to suppress the Military Orders again by confiscating their properties but reestablished them shortly afterwards.

In 1851 under the terms of the Concordat the Orders’ exempt ecclesiastical jurisdiction was preserved and some confiscated properties restored. The Priory of the four reunited Military Orders of Santiago, Calatrava, Alcántara and Montesa was established near Ciudad Real.

This period of turmoil and impending dissolution of the Spanish Military Orders provides the answer as to why in 1848 someone of the Spanish officer class in possession of very unique codes and charts undertook a mission to sail a ship known as the ‘Sea Foam’ across the ocean in secrecy to visit the cache.

What he sought to retrieve there remains unknown; certainly there have been no latter day sightings of any part of the hoard’s items arising out of Spain. But what would you be really able to do with them anyway?

He went there to gain access to the huge store of wealth, something which would have been more use to an Order fighting for its survival than any fancy candlestick. With him were three others. Thus begins the latter history of the great lost treasure.

The Latter History

The history of the event of the 1848 raid of the cache has passed into legend. As usual details of this were rolled into the previous stories to further obscure the trail and the identity of the treasure. However with careful investigation and a little help from Harold T Wilkins the identity of the participants and even the name of the ship they used, Sea Foam, is known. One of the members of this party was even still alive in the beginning of the 20th century and attempting to return to the island again for a 3rd (yes 3rd) time.

By this stage, the early 20th century, the way the story was being popularly told fell into two main limbs:

1. The ‘Loot of Lima’ on Cocos Island that John Keating left a map and directions for.

2. The treasure of the ‘Bosun Bird’ on a Polynesian island that a dying pirate named ‘Killorain’ had left a map and directions for.

The problem that occurred at this juncture was that though both Killorain and Keating spoke of going to an island and recovering the same treasure ( details of the Loot of Lima occurred in both the stories), no one seemed to bother to track down the other crew members or the ship that Keating was on. Nor did anyone track down the real names of the crew or ship that Killorain was with; Killorain and the other names given in the story being obvious pseudonyms.

If anyone did they would have worked out there was only one ship, the Seafoam, with a crew of four men who did not go actually go to Cocos Island but had sailed using the directions Ubilla had left with his Order that enabled them to return to the great lost treasure hidden on the Horseshoe island in the Trinity.

Enter Captain James Brown

Like most things in this whole story, the truth is clouded in deliberate fabrication. So too for the man known to many as Captain James Brown that made his presence felt around the 1900s (he was identified as being Scandinavian by birth so his birth name is unknown). A hulking Viking over 6 foot tall with a turned eye and huge club like hands, he roared out orders to sailors, made outrageous gaffes and had all convinced he was a barely literate ex-pirate who had plundered Australian gold ships in the 1850s. He inferred that he had murdered many and had relocated the Loot of Lima from Cocos Island to an unidentified island in the South Pacific.

The British Admiralty even had agents following his movements in the islands. Many thought this was due to the unpunished episodes of piracy he spoke of taking part in.

It was all an act.

Captain James Brown was actually a Freemason. Highly intelligent and extremely well read he could speak a number of languages. A master of psychology he was able to control those whose fell into his orbit and manipulate situations to his advantage. Through his activities and expeditions he kept all those he was with ignorant of what it was they were actually searching for and its location. He even acted out being the ‘dying pirate who is leaving a treasure map’ for those he thought would fall for it. He would then go on to made miraculous recoveries!

The extent of his knowledge can be uncovered only by researching the many ‘lost treasure island’ tales found in old newspaper articles and books. A method utilised by the Captain also displayed his understanding of the methodology required to make a fake story sound and appear real. The technique is to mix fact and fake together because the factual parts then can produce a gloss of credibility for the whole tale. The fake component can also be made more believable by simply copying some falsity from elsewhere, as repetition over time seems to provide a faint shine of factuality. This will be found to be occurring throughout many of the stories encountered in this and has been used repeatedly to great effect.

As a strategy Captain Brown would tell a different story to different parties to confuse all about what his secret really was. To make each story different he ended up adding unique details in each. By doing so he ended up inadvertently outsmarting himself. The Captain could never have foreseen that a hundred years after he told those stories reports of what he said could be easily collated and compared.

The Treasure of the Tuamotus

In 1939, a diver by the name of George Hamilton wrote and published, ‘The Treasure of the Tuamotus’. George Hamilton gives the story of the origin of the treasure he searched for as having come from a dying sailor named Killorain via a man named Charles Edward Howe but admits to having to “embroider a little” its reconstruction. George Hamilton became involved when he responded to an advertisement in ‘The Times’ in England in 1934 about a scheme for the recovery of hidden treasure. After an interview he became an investor in the ‘The Langham Marketing Rights’ syndicate and its diver for the expedition.

Charles Edward Howe was an ex-prospector that told many an alluring story. One night he had paid a kindness to a destitute old man. He was later summoned to a hospital where the old man, ‘Killorain’ lay dying. Killorain told him a story (there are different versions of the story that set it as occurring in Christchurch 1910 or Sydney 1912). Around 1849/50 Killorain and three others had stolen the Pisco church treasure after it was loaded on a ship named the ‘Bosun Bird’. They buried it on a Polynesian island. They then set sail to Australia and landed at either Darwin or Cooktown. Killorain was the last surviving member of this group of four. He left Howe with the map to the treasure and told Howe it was his for the taking.

The name of these four pirates were Diego Alverez, Luke Barrett, Archer Brown and Killorain.

Howe spent the years between 1912 and about 1926 on the island of Pinaki searching for the treasure. He was not there all that time, just when he gained enough money from either working in Papeete or being supported by investors who had listened to his story. Nothing was ever found.

It is made out that about 1920 he learned of a mixup in the names of two islands so he traveled to the correct island, unidentified in the stories (but now known to be Hiti) where the treasure is finally found. Rather than risking it being taken from him he re-hides some of the treasure. When he returned to Papeete the Police arrested him due to the investors complaining it was all a scam and he is deported. He ends up in Australia and tells his story to whoever listens. This story reaches the ears of a barrister by the name of William Graham who goes onto be instrumental in setting up the expedition that Hamilton was part of.

The expedition in 1934 that George Hamilton was part of was a disaster.

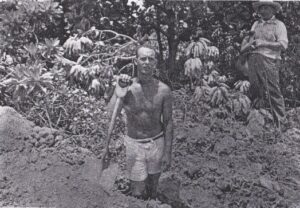

Nothing was found on Hiti so they went to a nearby island, Tuanake, just to check it also. On Tuanake Hamilton convinced himself that the gold was in a ‘pear shaped pool’ he has just found there so he vainly tried to excavate the pool’s sandy bottom. As this was going on accusations of the expedition being a scam reached the newspapers in London and the surrounding bad publicity shut the enterprise down. Hamilton had to beg his way back to England as all his money had been expended on the trip.

The 'historically accurate' story

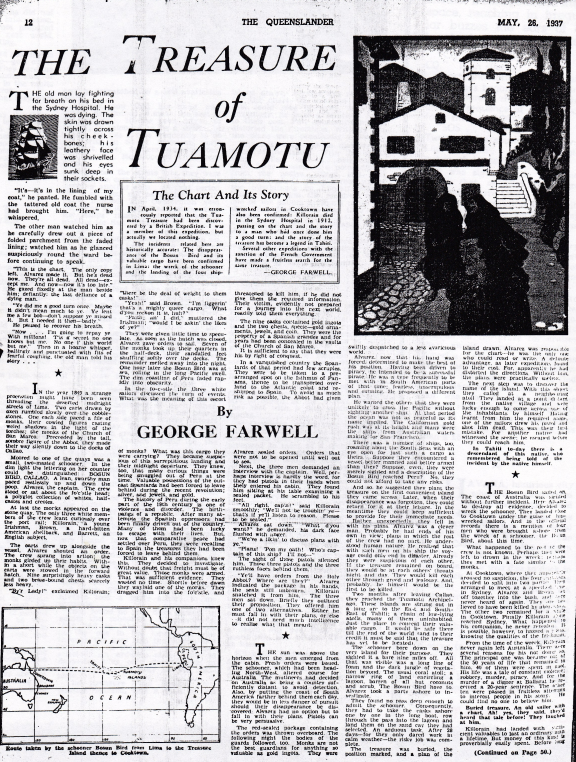

There is a little known version of the story by George Farwell who was on the same expedition as Hamilton. What you didn’t know was that he was a writer and his version was published as an article in ‘The Queenslander’, an Australian journal in 1937.

When searching for information about the story of the Bosun Bird, Farwell’s account never seems to be mentioned. This is not so much because it was published in a small journal in Australia but rather it pricks the bubble of illusion Hamilton sought to inflate about the treasure. The article is titled ‘The Treasure of Tuamotu’ and an inset immediately beneath this heading makes this statement;

“In April 1934, it was erroneously reported that the Tuamotu Treasure had been discovered by a British Expedition. I was a member of this expedition, but actually we located nothing.

The incidents related here are historically accurate: The disappearance of the Bosun Bird and its valuable cargo have been confirmed in Lima: the wreck of the schooner and the landing of the four ship-wrecked sailors in Cooktown have also been confirmed: Killorain died in the Sydney Hospital in 1912, passing on the chart and the story to a man who had once done him a good turn: and the story of the treasure has become a legend in Tahiti.

Several other expeditions with the sanction of the French Government have made a fruitless search for the same treasure.”

None of it was true. The Bosun Bird never existed, no treasure was stolen from Lima and Killorain didn’t die in Sydney Hospital. Cooktown wasn’t even built until 1872, more than 20 years after the date this was all set and is a fact easily checked by any Australian.

So ends George Hamilton’s part in this and this was the state of affairs for him in 1939 when he tried to tell his story to get others interested. Hamilton (full name George Hamilton Snowball) never recovered financially from the expedition and his reputation suffered. Any publicity that Hamilton was attempting to generate for another expedition via the publication of his book was lost in the turmoil of the Second World War that engulfed the world that same year. Fate dealt him another blow when the Luftwaffe bombed his house. The resulting fire destroyed most of his possessions and the documents he held pertaining to the expedition. He died in the 1970s ruing his involvement in it all. The surviving members of his family want nothing more to do with the story.

The problem with it all was that no one actually checked any part of the story they got from Howe. If they had, and you would have thought a barrister would have, they would have discovered that many of the details held out as fact were just not true; the history as said was impossible as the locations identified in Australia weren’t even in existence yet. The story as spun was just a conglomeration of about every popular treasure story getting around, from Drake’s mule attack on Nombre de Dios to the Loot of Lima to others ones just lifted near word for word from popular books. No one even checked that a ‘Killorain’ actually died in hospital. Perhaps if they had checked and learned that that part of the story was fake then they might have gone on to discover that the man Howe called Killorain was very much alive after 1912 and was still trying to get back to the island.

Hamilton lied to some extent in his book and of course Howe lied to some extent also. Howe himself was unaware of the origin of what he himself had been told. To what extent all were misled by the same man has never been known until know.

Diego Alverez, Luke Barrett, Archer Brown and Killorain on the Bosun Bird.

Do you have any idea of the origin of these names?