The Real Raiders of the Lost Ark

“Four men”, Howe had was quoted as saying, “had a hand in the business, a Spaniard named Alverez, an Irishman named Killorain and two others of uncertain nationality, Luke Barrett and Archer Brown.”

Because of the amount of subterfuge, deliberate misleading and confusion about the treasure it is much easier if you start knowing about the Sea Foam and go on from there. Captain James Brown told stories of the origin of the treasure. Like all good masonic tales these were metaphors of the real thing, designed to cloud the treasure’s identity and location. To work through it all it is necessary to first know the real names of the crew.

Captain Brown is immediately recognizable. In the 1840s he was still in his teen years, so Captain Brown’s involvement could not have been that of command of any such operation. Due to his age he was a junior crew member of the Sea Foam. Inquiries around 1901 verified the ship as having been sighted in Dulce Bay prior to it going ‘pearl fishing’. Other enquiries verified that when young, Captain Brown had once had a lot of credit in a London bank. Though not ever expressed in the reports about Captain Brown, it has been identified that he knew not only the meaning of the Trinity, but the exact layout of the Trinity group of islands. Whoever was in charge of the Sea Foam then was utilising and understood the meaning of the Spanish directional codewords.

The person called ‘Killorain’ was next in seniority. Wilkins gives you the clues to find his real identity. In ‘Pirate Treasure’ and ‘Modern Buried Treasure Hunters’ placed next to a story about an ‘aged sea captain’ (Captain Brown) are the details of Roland Kelley. Wilkins, for the person who was following his real clues, grouped the related details together in sections of his books. This way the links could be explored and established.

In 1913 Kelley was an undergraduate at Harvard University when his grandfather bequeathed him a large fortune. The receipt of the fortune was conditional upon Kelley searching out a treasure prior to his twenty first birthday,

“Roland Kelley had to find certain pearl fisheries and a treasure on two uncharted islands in the Pacific. The islands, said the will, were found by the old mariner, his grandfather to have a large amount of gold. He lit on them on one of his voyages when he was searching for freshwater. The pearls were seen on another voyage.”

An enquiry directed to Harvard University has confirmed the existence of one Roland Paddock Kelley. Born 24 May 1894 at Brockton Massachusetts he was the son of Frank Leslie Kelley. Roland Kelley attended Harvard between 1911 and 1915. The name ‘Paddock’ is a version of an old English name for ‘frog’ but more normally appears as a person’s surname. Here it appears as Roland’s middle name. His middle name, Paddock, was most probably the christian name of his grandfather, Paddock Kelley. Whatever directions were left to Roland was not enough for him to find the treasure.

Next in seniority on the boat was John Keating. Captain Brown’s alias for him was ‘Luke Barrett’. This was just a continuation of the form of the names given in other stories being, Tom Daggett in ‘The Sea Lions’, Tom Gammage in ‘Captain Kidd’s Gold’ and Tom Sinnett in various versions of the Trinidade Island treasure tale. All the history about him identified he was on a ship that first went to Dulce Bay on the pretext it was then going ‘pearl fishing’ in the South Pacific. Due to his knowledge of the Star Code as they applied to the island’s position Keating was most probably of the rank of Bosun and had navigated the Sea Foam there. His legacy was to re-direct everyone to Cocos Island after whatever indiscretion it was enabled Fitzgerald to glean partial directions from him.

The actual identity of ‘Diego Alverez’, will remain an enigma. It was a clever pseudonym used by Captain Brown built around the name of Diego Alvarez Island.

Known today as Gough Island, it was first marked by Goncalo Alvarez who discovered it in 1505. The island was given his name and on early charts appeared as ‘De Isla Goncalo Alvarez’. It was later shortened to ‘De I. Go. Alvarez’, then to ‘Deigo Alvarez Island’ before becoming ‘Diego Alvarez Island’. The real clue about the name is discovered in Ralph D Paine’s 1911 book ‘The Book of Buried Treasure’ in which there is an entry of great import that speaks of the landmark of the Pan de Azucar;

“Gough Island, sometimes called Diego Alvarez. Latitudes 40 degrees 19’ S. Longitude 9 degrees 44’ W. It is well known that on this unfrequented bit of sea-washed real estate, a very wicked pirate or pirates deposited ill-gotten gain. The place to dig is close to a conspicuous spire or pinnacle of stone on the western end of the island, the name of which natural landmark is set down on the charts as Church Rock.”

Apart from descriptively being one of the same directional landmarks Hamilton sought on his ill fated expedition, Church Rock is actually a sea stack (a tall column of rock) in the water to the north east of the island.

The name given for their ship, the Bosun Bird, also has its origin in the name of an island.

When Benito de Soto attacked the Morning Star in 1828 it was near to Ascension Island. Two hundred and seventy metres to the east of Ascension Island can be found Bosun Bird Island named after the Bosun Birds (or Tropicbirds) that inhabit it.

All that is known is that the real ‘Alverez/Alvarez’ (the spelling was given both ways) was a Spanish nobleman who must have been a member of the Order of Santiago, the same Order that Ubilla had been a member of. This was the only way ‘Alverez’ could have had in his possession or understood the Star Code in their Alchemic form to direct the Sea Foam to the island.

Whoever he was, he was the Captain and Commander of the Sea Foam and had scared the rest of the crew enough, even the fearsome young Brown, so that his identity was never spoken of. They all maintained absolute secrecy about his involvement in the affair.

How the three men, John Keating, Paddock Kelley and James Brown came under the command of the Spaniard will never be known, suffice to say he had chosen them well as the wall of secrecy they surrounded the treasure with was upheld by them even after their deaths.

Honest Charley Howe

For his part in all this, Charles Howe diminished and obscured his interaction with Captain Brown. Howe was entirely successful in this as the expedition Hamilton was part of were entirely unaware Captain James Brown was Howe’s source.

Captain Brown had originally been very well off after raiding the hoard all those years ago. He returned once to replenish his funds in the latter half of the 19th century but a series of events later, including the confiscation of two of his frigates for gun running, forced him to consider returning to the hoard. Now aged in his seventies he sought out others he could trust to facilitate this.

What follows next is the history of what was really going on behind the scenes surrounding the lost Trinity of Captain Brown.

1901: Captain Brown appears in San Francisco. On his sick bed he tells a strange story to a fellow Mason (a Dr Luce); that years earlier he had been on a ship that had relocated the Loot of Lima from Cocos Island to an island in the South Pacific. He then went on to pirate Australian gold ships thereby adding more gold to the hoard. The crew of the ship he was on, the Sea Foam mutinies and Brown and two others sail a small boat with some gold to Australia. Brown is the only survivor to go ashore.

After a Lazarus like recovery, the result was an expedition to the South Seas in 1902 (which left finally from Sydney, Australia) known as ‘The Voyage of the Herman’. Those who took part in the expedition checked out as much of the Captain’s story as was possible, even to tracking down that the Sea Foam had been in Callao around the 1850s. The expedition never went anywhere in particular other than cruising around some Polynesian islands. Details can be found in the book of the same name which comes from the records of the Herman’s captain, George Sutton. Another book, ‘Our Search for the Missing Millions’ written by a participant of the expedition, John Chetwood, reiterates the same details about the expedition but in the author’s ironic and self deprecating manner.

Captain Brown proved to be a mass of contradictions and most of the participants didn’t know what to make of him or how to control him. At some stage they began to have thoughts Captain Brown was trying to engineer a takeover of their ship. Captain Brown refused to disclose the location of the correct island so they all went home thoroughly fed up. There had been ongoing interest of the expedition by the British Admiralty which had agents tailing the movements of Captain Brown. They subsequently surmised that the Admiralty panned for Captain Brown to unearth the treasure then apprehend him with the evidence of his piracy.

Captain Brown didn’t just bow out disgracefully though with the end of the Herman expedition, he carried on for years attempting to return to his island. Nor did the Admiralty interest in his exploits end with the Herman.

Robert I Nesmith ( a writer from the 1950s) gives a sketch about Captain Brown who is described as “a great hulk of an ex-pirate”. A New York backer took the Captain for the recovery of the Cocos Island treasure. Captain Brown became vague as to which island it was on but was finally made to put up or shut up. The Captain picked an island, pointed to a spot and said, “It’s right around here” before collapsing and passing out. Nesmith does not give the date of this anecdote.

1909: our Captain persuaded another syndicate to try for the treasure, this time from Boston. They sailed for Australia on the ‘Mariposa’ (this was the same vessel that returned Sutton, Chetwood and Luce back to San Francisco). Captain Brown and his suitcase full of maps then departed from Sydney in a sailing ship to retrieve the treasure.

Chetwood had written to Sutton about this expedition and of the Admiralty’s ongoing interest. Upon reaching Tonga, Captain Brown “said he sighted his bloody island but just then a storm broke and drove him back on the New Caledonia reefs-as reported in the press.”

In July the same year, another syndicate from Boston backed Captain Brown. The steamer ‘Ethelwold’ (a British fruit ship) was chartered in New York. The ship did not leave New York harbour. It is unclear what transpired but was something to do with “mysterious events”, “contraband” and “Internal Revenue Agents”.

1912: Captain Brown was in Sydney. He then acted out the role of the dying/sick pirate to Charles Howe, somewhat as he acted out the role a decade earlier for Dr Luce. In the drama he was acting out for Howe though the characters of Alverez, Killorain and Luke Barrett were named as the other crew members. Howe, when he told the story later, just switched around the names of Killorain and Brown so Killorain was now the sole surviving member of the gang. Thankfully Howe’s imagination wasn’t up to the task and Captain Brown’s physical features crept into Howe’s narratives: Alverez was described as having huge club like hands and a turned eye.

One major piece of the puzzle was given by Captain Brown himself when he sent a letter dated 19 March 1912 to Sutton. Referring firstly to the failed 1909 expedition, Captain Brown goes on to inform Sutton that he had been contacted by a “party” interested in fitting out an expedition “but they want to go by themselves, & that I do not care about very much.” This was the date Howe left for his searches of Pinaki armed with Killorain’s map and directions. For Howe, whatever he was told by Captain Brown indicated to him that two or even less people could effect a recovery of the treasure. Due to the amount of subterfuge in disguising Captain Brown as his source, it appears Howe believed the treasure to be tainted by illegality. The suggestions of piracy given by Captain Brown would have given rise to this belief. In Howe’s mind it would not have assured his title to the recovered gold. Captain Brown for his part must have considered Howe the most suitable match and so provided him something else no one else was ever given; a map that marked the treasure and the location it pertained to.

Whether Howe thought he might meet with an ‘accident’ if accompanying the Captain by himself or he just absconded when he was given the map and directions will never be known.

Captain Brown was a bit smarter than that though; he withheld important details of the treasure’s actual location resulting in Howe wasting many years of his life in a fruitless search.

1919: Charles Nordhoff visits Pinaki and finds Howe there. On the island’s northwest sector Nordhoff observes Howe probing the bottom of the inner lagoon. He is also shown the long lines of trenches Howe has excavated in the sand looking for the treasure. Nordhoff does not actually name Howe in his book ‘Faery Lands of the South Pacific’ but relates the story of the treasure as it was told to him. It is a different version again. Howe shows Nordhoff something interesting; a large block of coral stone inscribed with strange symbols that Howe wistfully puzzles over.

Unbeknownst to Howe and Nordhoff these are what is known as ‘Spanish Treasure Symbols’ and are the doctrinally mandated symbols that are the navigational directions to the treasure.

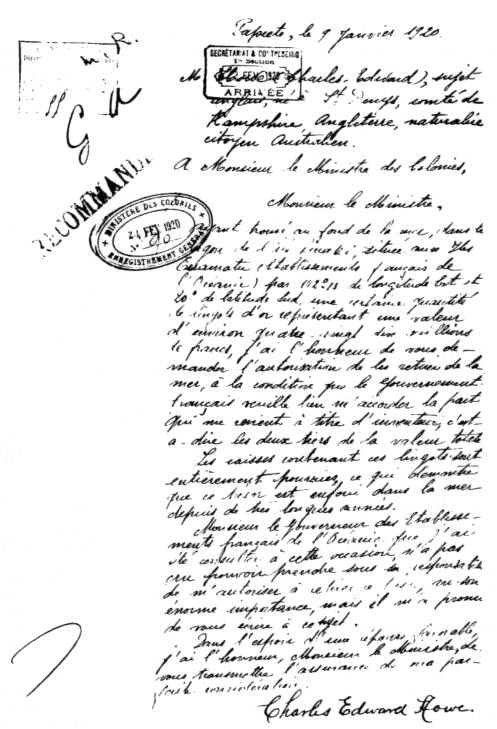

Please excuse the poor translation but the important parts are;

“…….having found on the bottom of the sea, in the lagoon of Pinaki Island (Tuamotus Archipelago) by 142 degrees 11 long west and 20 degrees latitude south some quantity of gold ingots representing a value of 86 million francs…..”

“……I would like to ask you the authorization of getting the gold and to keep 2/3 for me as finders rights…..”

“……the boxes containing the gold are completely rotten. That proves they are in the water a long time….”

1919: The Brown Exploring Company was incorporated. Captain Brown, by now 89 years of age, died before the expedition organised by Captain T. Houghton sailed on the schooner ‘Gennessee’ to find the treasure. With a compliment of 36 personnel on board some subterfuge was necessary to keep the real purpose of the expedition a secret till the last minute. A cover business, ‘The South Seas Pacific Film Company’, was used to engage adventurous men as the crew for a cruise to the South Seas. They were initially told they would be the cast of a pirate movie being shot on location in the islands.

The following report appeared in the New York Sun, June 17, 1920.

“On February 27 (1920) we sailed out of Tahiti for an island in the Tubuai group. We left our craft outside the harbour of a beautiful island and went ashore. Excitement ran high as news of the search spread among the crew. Captain Crowley, (Arthur L. Crowley, of Boston) was armed with maps and charts. The point we sought was inland, and we found a mound where the treasure should have been. We began digging and continued to dig for three weeks, uncovering a huge area. But we found only the bones and we finally gave up the task.”

Though this report says the island is in the ‘Tubuai group’, Tubuai is an island in the Austral Group. The island they went to was Tupai, which is in the Society Group. Tupai was sometimes spelt Tubai and due to the involvement of the real pirate ship, the Araucano, which was associated with both Tupai and Tubuai, this spelling mix up often occurred.

1921: an apocryphal incident regarding Howe occurred. Howe was working in a curio store in Papeete to gain finances for provisions for his next trip to Pinaki. Unlike what is said in the other stories about him, he didn’t spend all his time on Pinaki atoll. Two locals walked in offering help in the search for the treasure. They were the brothers Juventin. Howe told them the place to look was in a hole in the lagoon on Pinaki and described the location. A mis-translation or misunderstanding occurred as he spoke to them because, after following Howe’s directions, when they landed on Pinaki they were shocked to find that what they had understood to be a shallow pit in the lagoon was in fact a deep hole. The equipment they had bought was completely unsuitable to plumb such a depth looking for treasure. They returned to Papeete and angrily confronted Howe who looked at them impassively. As far as he was concerned he had told them where it was, it was their fault that they could not do anything about it.

(According to Hamilton it was in 1920 that Howe was supposed to have abandoned Pinaki and traveled to the other island and located the gold there. Yet here we have a letter signed by him in 1920 to the French government claiming the gold was on Pinaki as well as sending the Juventin brothers there on their futile trip. Between Hamilton’s expedition that went to Hiti and the French authorities, Howe was claiming he had found the gold on two different islands.)

circa 1920-21: Howe had learned of the Gennessee expedition and considered Captain Brown had in some way misled him. But as the Gennessee expedition had not found the gold either, Howe had then commenced a search for another Trinity group of islands, thereby discovering the Hiti Trinity at 16 degrees 45´ South, 144 degrees 5’ West, around the same latitude of the Tupai Trinity, but much further east. He searches there but locates nothing.

1926: The western writer Louis Lamour is on a freighter in the South Pacific. He records in his diary that an English warship intervenes in a gun battle near the island of Pinaki. Why an English warship is in French waters and what this gun battle is about remains a mystery.

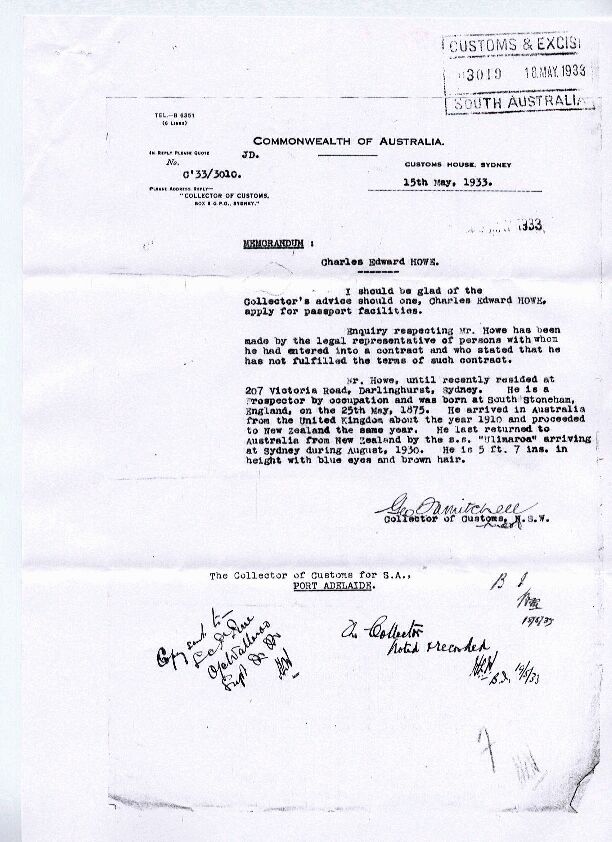

1926-1934: Howe drifts around before getting William Graham interested in the story. Howe disappears just prior to the ‘The Langham Marketing Rights’ expedition group arriving in Sydney. His last known location is in Armidale which is a town in New South Wales. All attempts to trace him fail.

There was a simple reason for his disappearance.

Graham, the Barrister, had made Howe enter into a formal legal agreement to guarantee his participation and performance in the expedition. For Howe, this was no mere pair of local brothers who could only vent their anger on him. This was a fully-fledged expedition that was expending considerable amounts of money. Howe knew he would be sued by the expedition when they failed to find the gold he claimed was on two different islands. With a contract comes liability if the contract is not fulfilled. He did the only thing possible, he went missing and stayed missing.

Searches by the police and private detectives at the time failed to find him or a record of his death. His last known location was in Armidale, New South Wales, from where he sent a letter claiming he was ill. Howe was actively hiding rather than just being missing.

He remained in hiding for the next decade until a record of his whereabouts was created he could do nothing about. Charles Edward Howe died in 1945; his death was registered in the small New South Wales coastal port of Bellingen, which is relatively near Armidale.

The Spanish treasure code

Spanish coded symbols have been in use since the 16th century when the Spanish were conquering the Americas. As a method of security coded signs and symbols were used extensively to mark the route to valuable mines or lodes of ore. The Kings of Spain had decreed that any such wealth generating enterprise like as a mine had to remit back to Spain the ‘Royal Quinto’, a fifth of the wealth produced. To ensure the flow of the Royal Quinto was uninterrupted, the use of coded signs and symbols as route markers to wealth generating locations was mandated and their format standardised. These signs could also be used wherever the Spanish had to cache items, such as abandoning a mission temporarily or safeguarding valuables at the site of a shipwreck whilst survivors went for help. The code was not just about the marking of rocks, it also related to the placement and arrangement of unmarked stones as camouflaged monuments and directional pointers. This does not mean that everyone was privy to the code’s workings. To ensure security, knowledge of the code was reserved for the officer class only, such as the Commander/Master, his Executive Officers, Surveyors and the Padre. Part of a translated document describes the extent of the resources assigned to this task for a large expeditionary enterprise;

“In the first place the location was selected and subsequently surveyed, also with great care, and the rocks and markings placed in proper place by men who had no other purpose or responsibility. There were ten men whose only responsibility was to mark the rocks with extreme care and place them in their proper place. Fifty men were officers, who directed the work, a number of surveyors, blacksmiths and botanists.”

Even though there was a regime of standardisation, there was still a subjective element to the encoding/decoding. This was due to the overarching influence religion had upon the Spanish. The Bible (the Old Catholic version), being a standardised text, was used to a great extent as a ‘code’ book as it would accompany the Spanish everywhere. Lines of coded directional text could be easily plucked from it, eg. “And she arose to go from the land of Moab to her own country with both her daughters in law.” (The Book of Ruth 1,6 or ‘go northwest’). It is worthwhile then to try and discover the religious influences or doctrine operating upon the particular group who may have left the coded instructions. Each Order, for example the Franciscans or the Jesuits etc., have their own favourite Saint and so prefer that Saint’s teachings. Likewise an expedition Commander or ship’s Master may have had their own particular patron Saint or had been schooled by a particular Order. This knowledge could then provide a clue as to which book of the Bible may have been used for the code and how the teachings within that book should be interpreted if used for directions.

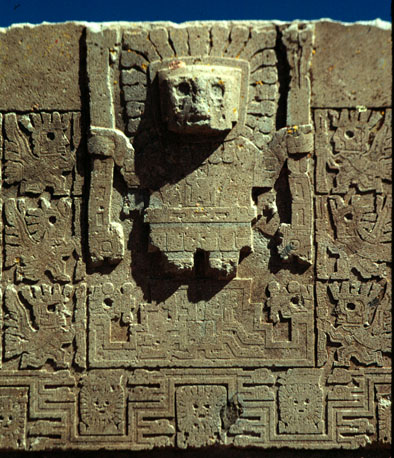

Examples of basic doctrinal Spanish treasure symbols

If units of linear measurements are found being given as part of any of these directions then it is the old Spanish units that must be used. These are both numerous and bewildering, the smallest being a Punto (point) which equates to .000354 of an inch. The Spanish ‘inch’ was a Pulgado being .914 of an inch. Just be aware that one of the most common units was a Vara. This was regulated unit being the distance a walking Spaniard would pace in one stride. It equates to 32.5 inches. 5000 Varas then makes up a Legua, about 2.52 miles. A person instructed to walk say 750 paces could use the regulated distance set for the Vara to obtain an exact measurement. An Estado was two Varas which is 65 inches. A Braza was a nautical unit of measurement and was the Spanish equivalent of a Fathom. It was the same distance as an Estado.

Likewise the Spanish engineering employed to conceal valuable items was just as extensive and detailed. With labour in plentiful supply in the form of the enslaved Indians, nothing was spared. Chambers were hewn out of the living rock, hillsides collapsed, solid vaults of masonry were constructed underground and even the diversion of rivers or the creation of lakes were undertaken to hide any trace of the site.

The Spanish symbol/sign code is too voluminous and extensive to give anything but this brief introduction. Even so, the circle with the dot symbol that was cut into the rock on Pinaki should already be recognisable as it is the chemical symbol for gold. It is also the symbol for the sun and god.

The 3 important rules to know about in regards to Spanish coded instructions are:

So prolific were the use of these signs that we get from them the well-known phrase always imaginatively associated with treasure maps; ‘X marks the spot’. The letter X was carved into rocks by Spanish surveyors as a marker for the inward trail to a mine or cache. X in fact doesn’t mark the spot at all. Signs point the way to other signs as guides only. The ultimate sign then points to the spot which itself is left unmarked.

When a deposit is exhausted or a cache retrieved the signs are destroyed. Allowance should be made for the likelihood of the cache or whatever being found by a non Spaniard who didn’t bother to follow the rule.

Caches could only be buried at depths based on the Estado. The minimum depth was one estado then only at multiples thereof (eg. 5’ 5” then 10’ 10” etc). If the buried cache was of nautical origin then the unit of depth was the Braza that was just the same anyway.

The Sea Foam

The name of the ship crewed by the raiders of the hoard, Sea Foam, may be just the anglicisation of its actual name, the Viracocha. Viracocha, the name of the Inca creator god means ‘Sea Foam’. Spanish conquistadors claimed in their accounts that they were referred to by the Incas as ‘viracochas’ due to their white skin and beards. Those of the Atlantean line of philosophy, of which Harold T Wilkins was one, believed that the ancient indian civilisations in South America were founded by the survivors of the deluge which sunk the continent of Atlantis. Legends of tall, white men wearing black robes who appeared one day to share their advanced knowledge are pointed to to support this idea.

When the origin of the name ‘Sea Foam’ is known it brings a new understanding why the ship used by the Spaniard to visit the great lost treasure had this name.