Harold T Wilkins

The Captain Kidd's Treasure Charts hoax

Richard E Latcham

Harold Tom Wilkins (1891-1960) was an English writer from the last century whose body of work mostly reads likes the cranky ramblings of an eccentric. His literary output found its niche in the pulp trade. Prior to World War 2, the subject he dealt with in the main, pirate treasure hunting, was the most popular interest of the time. This was reflected in the number of books he published with titles such as ‘Pirate Treasure’ or ‘Treasure Hunting’ or the numerous articles he wrote with imaginative titles like ‘Maps Spur New Hunt for Kidd Treasure’ for magazines like ‘Modern Mechanics’. His other interest was technology. One book he wrote was, ‘Marvels of Modern Mechanics’ and he had a keen interest in the development of television and wireless communication, even corresponding with John Logie Baird, the father of TV. Briefly after the Second World War his bent was for books examining how ancient civilisations in South America could be traced to their Atlantean origin. He then took up the new subject on everyone’s lips; Flying Saucers. The mind of Wilkins however was operating at a level far above and beyond his average reader which was why his plan to clandestinely pass the secret to the lost treasure of God in the form of a hoax riddle was so successful. That and the complete lack of common sense by those who thought the hoax about Captain Kidd’s Treasure Charts was real.

Anyone researching the history of ‘lost treasure stories’ are forced to use Wilkins’ books on the subject due to their encyclopedic nature. These books reveal the considerable amount of time he spent poring over documents and manuscripts in the British Museum. A graduate of Cambridge and a linguist, he was fluent in Latin and Spanish and his translations of the manuscripts he referred to in his books even went as far a footnoting an ambiguous term or meaning.

His main books on lost treasure were published over a period of nearly two decades:

1929 Hunting Hidden Treasures

1934 Modern Buried Treasure Hunters

1937 Pirate Treasure

1937 Captain Kidd and his Skeleton Island

1939 Treasure Hunting

1940 Panorama of Treasure Hunting

1948 A Modern Treasure Hunter

A prerequisite to be able to even commence to follow the clues and hints Wilkins placed in his books is to have a large amount of prior knowledge of the subject already. Only then can you begin to realise what he is alluding to. Once a sufficient level of background knowledge in the subject has been attained, to read his books is like a having a private conversation with him. An understanding can be had about what Wilkins is really speaking about even if he does not directly express it. The background knowledge already obtained via this website is sufficient to begin to find his clues. The clues he left for the riddle were cumulative, you had to have them all. And they could stretch across the world to where he left them. Still, you can find them if you do the work and do not just blindly accept or follow what was written by previous commentators or ‘experts’ of these fabricated maps.

The background to this all is that sometime in the 1920s Wilkins discovered Lord George Anson’s file languishing in the British Museum.

The file, after it had been copied and passed around after Lord George Anson’s death, had eventually ended up in the British Museum as such papers did, the museum being the early equivalent of the National Archives. It simply became lost among the British Museum’s vast un-catalogued collection of manuscripts, books, maps, files and letters that had been accruing since the museum’s establishment by Act of Parliament in 1753. This collection had grown to such unwieldy proportions that a cataloguing program commenced in 1898 to identify and give order to the holdings took until 1922 to complete.

He decided to carry on the fine tradition of making up a hoax/riddle story about the lost treasure of the Temple but this time put the real details from Lord George Anson’s file within it. Wilkins, through his extensive research, knew already that all the ‘lost treasure island’ stories had their basis in the history of this lost cache.

The whole thing for him was a comment about the blindness of treasure hunters around the world who did not realise they were all following the same story. He made the whole thing doubly damning by putting the real details and actual map right in front of them to find yet they still didn’t see it. He even gave instructions in his book ‘Panorama of Treasure Hunting’ about how to produce fake maps.

In summary;

a. Obtain a blank page torn out of a late 18th or early 19th century book (this provides paper of the correct age if tested).

b. Use a blunt pencil or a dirty brush to execute the work.

c. Don’t use a modern outline of the island being drawn.

d. Make sure the lettering style is correct for the period.

e. For Cocos Island slip the map into a book published between 1820 and 1837 that deals with arithmetic, geometry, navigation or theology.

Even with those hints being given by Wilkins no one seemed to pick up that the ‘Captain Kidd’s Treasure Charts’ were just the size of book pages.

Wilkins also made a comment about a fake map he examined, the details of which are a clue even though he made it sound as if it is all just an invention by the map’s maker.

Written upon the map in “atrocious dog Latin” was:

‘Vista Interiora Terra

Rectificando Invenies

Occultum Lapadem (or Lapatem).’

Wilkins translated this as:

‘Interior view of the land, For rectification, thou shalt, or wilt find the hidden stone’.

The phrase Wilkins was alluding to comes to us from Alchemy via the acronym ‘VITRIOL’.

Along with this alchemic reference Wilkins describes a direction appearing on the map, “IX plus I” or “IV plus I” and then suggests this was a joke designed to “pass far above the sucker’s head”. Wilkins knew exactly what Lord George Anson’s file really said as he was fluent in Latin. One of his trademark clues though was to leave Latin phrases badly translated and let the ‘sucker’ try to follow what was some insensible phrase. ‘Blue Apples’ anyone?

Background information necessary to understand and follow the Captain Kidd’s Treasure Charts hoax/riddle

Wilkins had an extensive contact base he could draw upon to facilitate the hoax. The major players who assisted him are; Richard E. Latcham, Patrick Nolan, Herman Westhaver and R.A.Skelton.

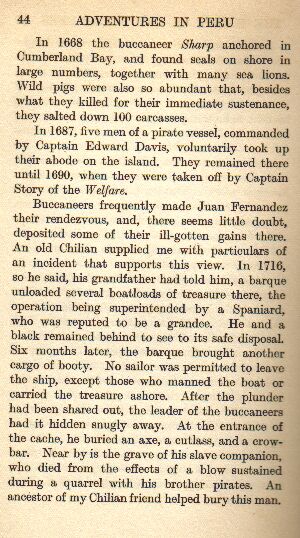

Richard E. Latcham (1869-1943) was an expatriate Englishman and mining engineer who is relatively unknown outside of Chile. He rose to being the Director of the National Museum of Natural History and was awarded the Chilean Order of Merit. Recognised as the eminent expert of native South American anthropology his book, “El Tesoro de Los Piratas de Guayacan”, (The Treasure of the Pirates of Guayacan) is regarded as an academic hiccup. A reference to Latcham appears in Wilkins’ ‘Modern Buried Treasure Hunters’ published in 1934. Wilkins tells of Latcham’s investigation into treasure documents found buried in a pot near the coast of Guayacan that belonged to the ‘Brethren of the Black Flag’. Latcham’s book on the subject, ‘El Tesoro de Los Piratas de Guayacan’ wasn’t itself published until 1935.

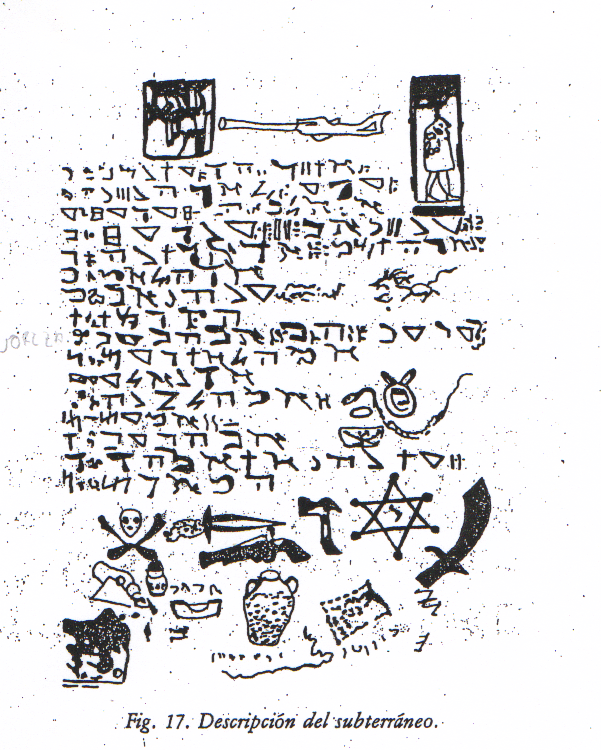

Written in Spanish, Latcham’s book is the strange story of how in 1930 he was sent by the Director General of Libraries, Archives and Museums to investigate a treasure hunt occurring in an area known as Bahia Herradura (Horseshoe Bay) at Guayacan. In the the northwest sector of the bay was the Playa Blanca (White Beach) where an expedition had arrived following a map. This hunt was unsuccessful but when the expedition left they gave the map to their local supply hand, ‘Castro’. Castro followed the map to uncover some artifacts, among them a copper plate and ancient manuscripts written in ancient Hebrew. These manuscripts (when translated) spoke of a multinational confederation of pirates who had used the bay as their base. Somewhere there they had established an underground fortress, a ‘subterraneo’, where they had strategically stockpiled supplies, arms, munitions and treasure. One of the treasure items was the ‘Rose of France’, “a miraculous rose, held in great esteem by all pirates and guarded carefully in the the treasure chamber.” These pirates had even recorded when Henry Drake, son of Sir Francis Drake, had sailed into their bay one day. The book is filled with bizarre and outlandish images of the Hebrew documents and their accompanying translations. Do you recognise some of the Spanish directional codewords and bits of Webb’s report appearing already?

Wilkins himself was also pretty forward about it all. In 1937 he published his book ‘Captain Kidd and his Skeleton Island’. The name itself is taken from Robert Louis Stevenson’s ‘Treasure Island’. The name ‘Skeleton Island’ comes directly from Stevenson in ‘Treasure Island’ is to be found “Captain Kidd’s Anchorage” marked on the book’s illustrative treasure map.

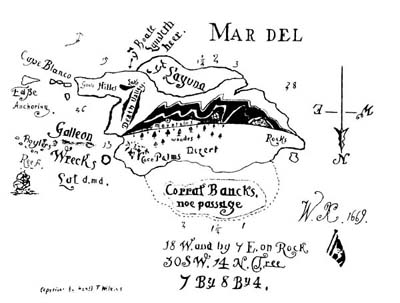

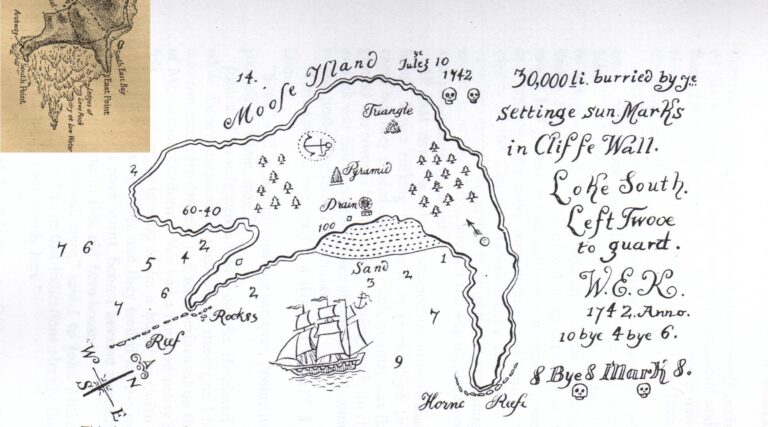

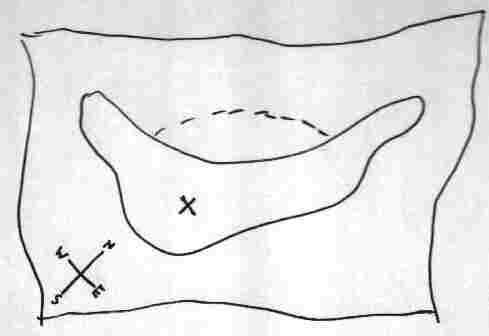

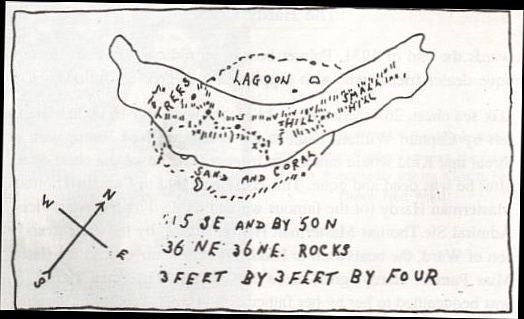

Included in Wilkins’ book were two maps he drew known as the ‘Mar del’ maps, an incomplete rendering of the Spanish phrase for South Sea, ‘Mar del Zur’. Note the compass pointing in different directions. For the purpose of the exercise in solving Wilkins’ riddle these maps will be referred to as W1 and W2 respectively. It was the bearings on the W2 map that caused the problem for Wilkins when Gilbert Hedden found they matched the stone datum markers on Oak Island.

Wilkins W1 map

Wilkins 2 map

In the chapter “The Skeleton Island of Captain Kidd” Wilkins pretends he had tried to identify the island shown on the maps by going through more than “800 Dutch, English and French charts”.

Wilkins then makes out he knows the island’s location;

“The historiography of this treasure island of Captain William Kidd is very curious and was unearthed by the author of this book only after prolonged researches. It would not be fair to the owners of the charts to disclose the name of this island, which in fact, has vanished from modern maps and does not seem to be known even to hydrographers and surveyors of the British Admiralty”.

He then informs that an old Portuguese “piloto” was the first European to sight the island as a record in the archives in Lisbon said,

“In 1525, in lat.-N they found certain islands standing close together, and passing among them called them after the name of the pilot, he being the man who first sighted them.”

The islands somehow became lost inasmuch as they were unable to be located by passing ships at the recorded position but;

“Then in 1803, the capricious mystery spirits again coyly lifted the veil. In that year a Spanish naval captain, bound from Manila to Mexico, sighted three coral-ringed lofty ‘isles’, which were not marked on his charts, and, in fact, were not believed to exist”.

Wilkins is giving a recognitive clue to the Trinity for apart from specifying that the place to look is three islands (not the single island shown on the Kidd maps) he is referring to the Sequeira Islands. These were a group of islands first recorded in 1525 by Diego de Rocha and named after his pilot Gomez de Sequeira. Subsequent explorers never located these islands again and it is assessed that the Sequeiras were just the result of the mis-sighting of other islands and the uncertainty of 16th century navigation. The island group in the area where the Sequeiras were thought to be are the Yap group at about 9 degrees 30 minutes North, 138 degrees 20 minutes East (of Greenwich). The longitudinal value of this group should immediately be recognised as being the same as the Pinaki Trinity. Wilkins then made reference to the sea shanty dealing with “Kidd’s angels, eyeless and ‘airless keeping watch in a valley.”

Patrick Nolan, also a mining engineer, was the ‘part author’ with Wilkins of ‘A Modern Treasure Hunter’ (1948). Within the book appears Herman Westhaver, a nautical pilot from Nova Scotia who, when interviewed by Wilkins in 1938, relates some ‘important’ information about some documents he found in a box under a marked stone on a haunted island. According to Westhaver,

“The treasure is at this moment, stored in a strong room, in the shape of a subterranean cavity, 18 feet long, the same width, 8 feet deep – from the floor to the roof, which is of heavy oak beams. The sides are strongly walled, and the top of the cave is four feet below the surface of the ground.”

He continued; “Besides the gold bars, gold dust, ‘dyamuns’ pearls and rubis, there are other articles stored in the cave, or approaches…there are fowling-pieces, old cannon, gun-powder and merchandise of different sorts.”

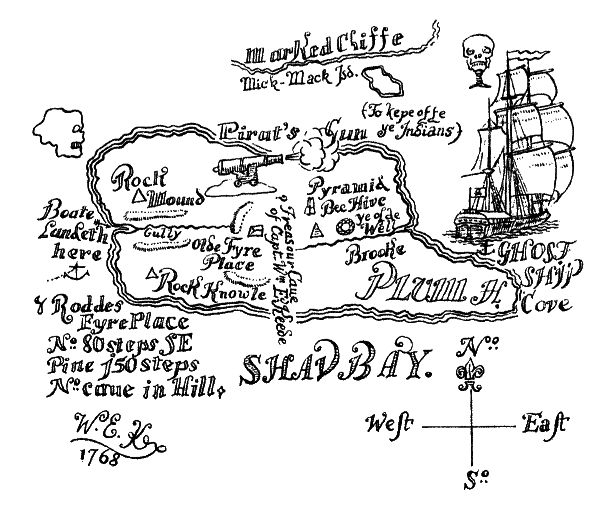

The maps found by Westhaver were said to display an island with three stone cairns set in a triangle. Wilkins provided two maps with this book known as ‘Plum Island’ and ‘Moose Island’. Both are laden with Masonic symbolism. So you didn’t miss the importance of the detail that the map of the island depicts three stone cairns he incorporated part of E.F.Knight’s map Trinidade Island. E.F.Knight also had a map of the ‘treasure island’ showing three stone cairns.

Some explanation is needed about these maps. Plum Island (left) displays the Masonic symbols ‘Pyramid’ & ‘Beehive’. The skull (upper left) is a representation of Cocos Island. On old maps Cocos Island was depicted in a somewhat crude way that resembled a skull. ‘Ye olde Well’ is partly a leftover from the original Spanish codeword for a ‘water source’ (aguada) but can be found also on old maps of Juan Fernandez Island as it marked a source of freshwater in Villagra Bay. Moose Island (right) replicates the Masonic symbolism again but includes an anchor symbol drawn on land (instead of in the water to mark an anchorage). This symbol is Masonic but can be more esoteric in meaning. The emblem usually is depicted with an Ark or ship. The Ark was the symbol of a guarded and concealed place of safety. The anchor is a modern development of the Caduceus of Hermes being a symbol of power and authority. The anchor is intended to convey the same meaning in connection with Temple or Lodge convocations. Therefore, in Masonic terms, the dual emblem means:

‘The depository of the secret and sacred papers or jewels of the Temple, and the power or authority of the assembled body.’

R.A Skelton was the Superintendent of the Map Room at the British Museum during the time when the fake maps were ‘discovered’. He authenticated the charts as being genuine. Did no one seem to realise he was in on the hoax also?

Cecil Prodgers

The Mechanics of the Hoax

Contemporary to the time that Wilkins was publishing his books on treasure, Guy and Hubert Palmer were wealthy bachelors in Eastbourne, England. The Palmers enjoyed their retirement by seeking out relics for their private museum of nautical and piratical history. Hubert Palmer was described at the time as being an authority on piracy and took a fancy to collecting anything associated with that well known pirate, Captain William Kidd. He was also described as being quite discerning, submitting items he intended to acquire to a thorough examination first to assure their authenticity.

The various descriptions given of Hubert Palmer does not tally with reality as a series of events that occurred over the next decade regarding Hubert and a few treasure maps indicate him to be rather gullible.

In furniture or relics that were fed to him were planted a series of maps. These were concealed in some way as it was known Hubert would rigorously inspect and test each relic he acquired looking for just such hidden things. Shown below, with the year they were ‘discovered’ by Hubert, are the series of maps known as ‘Captain Kidd’s Treasure Charts’.

They are shown here to comment on and demonstrate how obvious it is, even to a layperson, that some form of hoax was being conducted because;

a. The laws of probability must have been suspended for all these maps to serendipitously be in the furniture and chattels that ended up with Hubert.

b. They were all drawn on old paper the size of book pages.

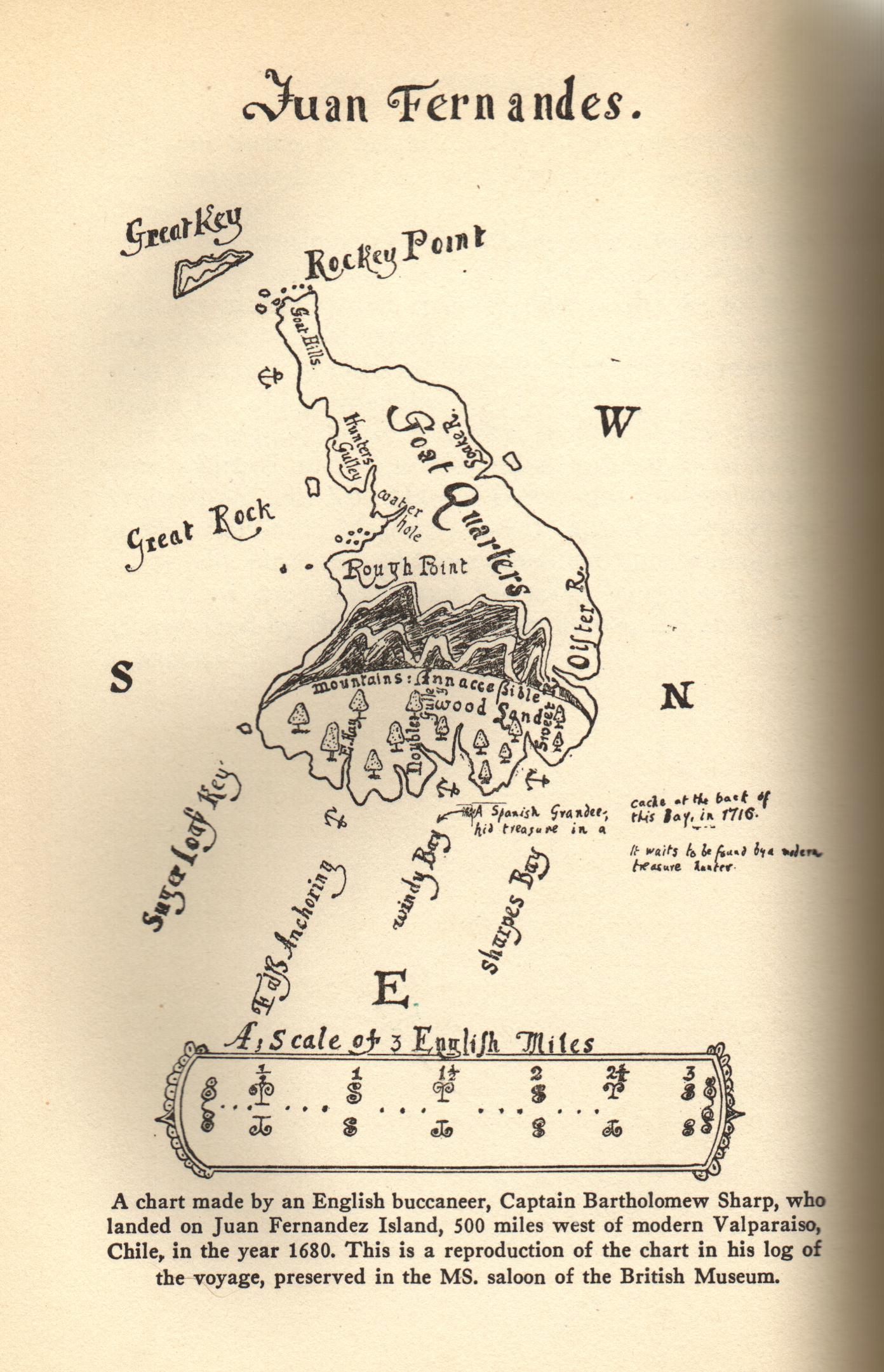

c. The first four are obvious depictions of Juan Fernandez Island with the ‘compass’ pointing to Cumberland Bay.

d. The style of the one from 1934 was copied from the 1897 book ‘Captain Kid’s Millions’.

e. The style of the one from 1942 was a copy of the ‘parchment’ from the 1888 book ‘Captain Kidd’s Gold’.

It seems though that none of this was obvious enough for the many Kidd experts who have argued themselves silly since the 1930s about which island it was that Captain Kidd had drawn on these maps.

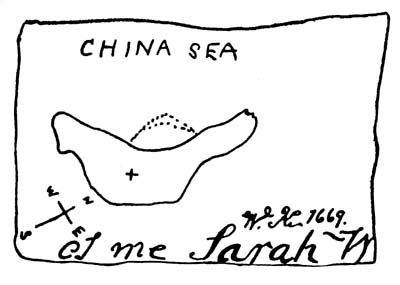

1929

1931

1932

1934

1942

Many Kidd map experts rely on the imprimatur of R.A. Skelton, Superintendent of the Map Room at the British Museum, who pronounced them genuine. Neither the British Museum nor the British Library (into which the Map Room was incorporated in 1973) have any copies of the maps themselves. Palmer had approached the British Museum to authenticate the maps and this work was coordinated by Skelton. Wilkins was very familiar with the facilities of the British Museum’s Map Room having spent numerous hours there researching old maps himself.

It is obvious that the images shown are not photos of the maps themselves but are some form of reproduction. The explanation as to why there are no photographs does strike at credulity, yet many have accepted it. Skelton simply said that the maps were so badly discoloured with age that they were not suitable for “direct photographic reproduction”. Reproductive copies were made instead by the “accurate tracing of a photographic enlargement”. This was an acceptable method of examination in the years when image processing on a computer was not even dreamed about by science fiction writers, but at least a photo of the image would accompany the reproduction to show the accuracy of the reproductive process. Here, the reproductions have now become the maps.

Overall this is no real problem as there is much testimony by those who compared the original maps to these copies and declared them to be faithful reproductions. It did take the focus away from the originals with the reproductions now being the subject of everyone’s examinations.

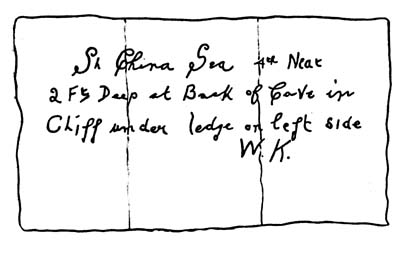

Apart from the excuse as to why comparative photos of the originals were missing, Skelton also supplied interpretations as to what the writing on the maps said.

For the 1934 map the notes Skelton supplied with the reproductive images suggested that,

“(3) The writing in the bottom right-hand margins is partially illegible. The following are conjectural readings, supported by certain extrinsic evidence:

(a) Bottom margin: ‘four….centre of triangle on to Rocks 20 feet’

(b) Right hand margin: ‘….E….Stakes….of Lake’

The trouble is, when the image is examined it plainly doesn’t say ‘….E….Stakes….of Lake’.

Skelton’s note accompanying the reproduction of the 1932 map said,

“In the line of numerals and letters reading ‘515 S E AND BY 50 N’, the numerals ‘51’ in the group ‘515’ are only conjectural, the original document is almost illegible at this point. “

By Skelton’s power of suggestion that is what these notations have become for many who seek to unlock the meaning of these maps.

Skelton was later to distance himself from his authentication of the maps. Fooling Hubert was one thing but when word got out about them then it was his reputation on the line.

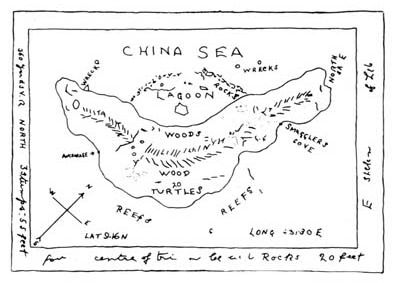

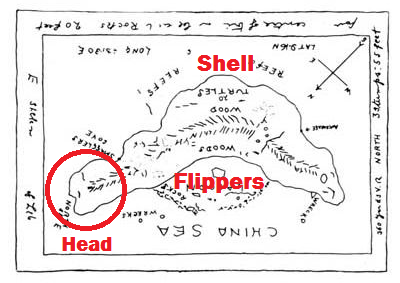

Why it was all was never solved before was that the Kidd chart experts just never recognised the clue in the form of an outlandish visual joke put on the 1934 map so they never progressed to the next part of the riddle. The ‘island’ shown on the different maps was obviously Juan Fernandez Island. The 1934 map even said ‘turtles’ meaning you turned it ‘turtle’ (upside down). If you did you would have had a laugh at the now obvious turtle displayed using the technique of trompe le oeil.

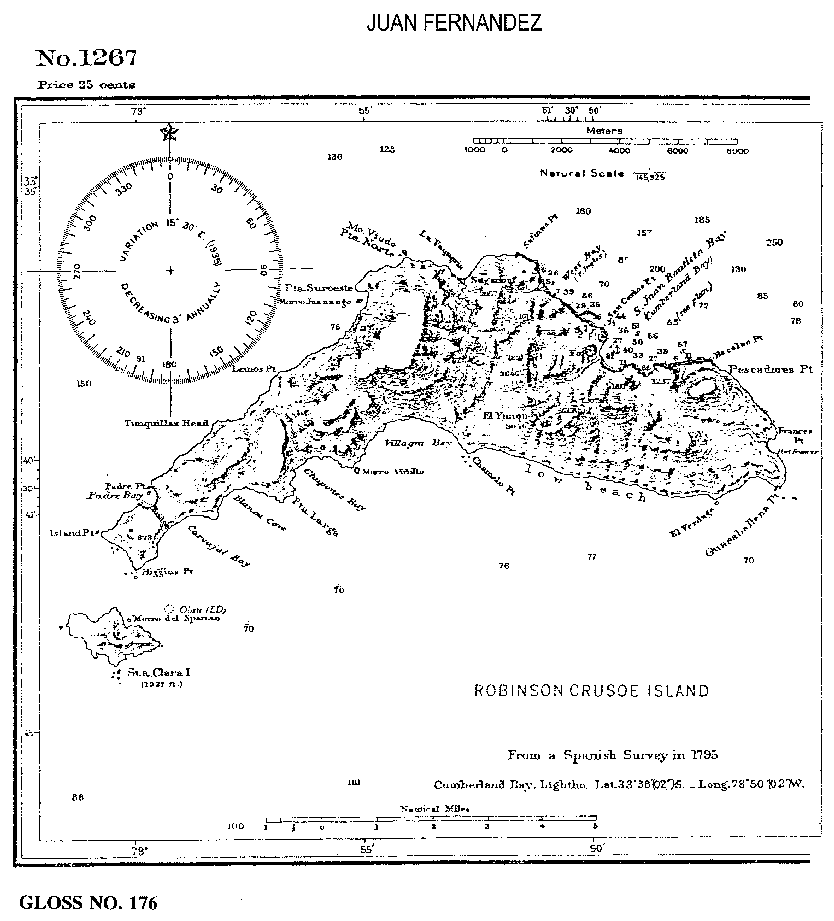

But that is just another clue in itself, for the next clue must still be tracked down and that is the chart that was used to create the ‘turtle’ map. It is this early 20th century 25 cent map of Juan Fernandez.

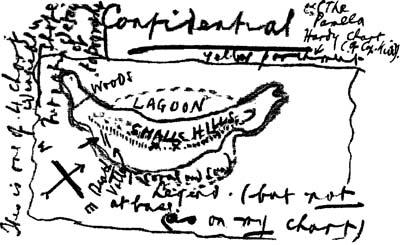

The notations read;

Left side and top corner: ‘This is one of four charts identical in shape but not in detail or topography’.

Top: ‘Confidential, The Pamela Hardy Chart (of Cap Kidd), yellow parchment’.

Centre: ‘WOODS, LAGOON, SMALL HILLS, Death Valley, coral and sand’.

Bottom: ‘Legend at base (but not as on my chart)’.

Many of the Kidd experts who have previously published books or articles attempting to identify the island they thought that Kidd had drawn on the maps will now try to claim they knew or suspected that the maps were not genuine at all.

All you have to do though is look at their previous works and if they didn’t identify that the maps were part of a riddle that led you to Juan Fernandez Island then you know they were duped by the hoax also.

There is only one location and that is the one Wilkins intended you to find by solving the riddle. But it’s not Juan Fernandez Island either. Knowing the maps were showing Juan Fernandez was only a stage in the riddle’s solution.

Wilkins was referring to a location given in Lord Anson’s file, Webb’s report and on Ubilla’s map and it’s another location entirely.

He even gave it right in front of everyone’s nose. Yet like the turtle on the map no one saw it.